GMJ Medicine

eISSN : 2626-3041

Volume 2, Issue 3 (2023)

GMJM 2023, 2(3): 97-100 |

Back to browse issues page

Article Type:

Subject:

History

Received: 2023/02/22 | Accepted: 2023/06/17 | Published: 2023/08/3

Received: 2023/02/22 | Accepted: 2023/06/17 | Published: 2023/08/3

How to cite this article

Mohammadipour Anvari H, Sadeghi S. Comparison of Ondansetron and Metoclopramide in Prevention of Nausea and Vomiting after Coronary Artery Bypass Graft Surgery. GMJM 2023; 2 (3) :97-100

URL: http://gmedicine.de/article-2-202-en.html

URL: http://gmedicine.de/article-2-202-en.html

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Rights and permissions

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Authors

H. Mohammadipour Anvari *1, S. Sadeghi1

1- Tuberculosis and Lung Disease Research Center, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran

Keywords:

| Abstract (HTML) (1407 Views)

Full-Text: (160 Views)

Introduction

One of the major problems for patients and medical staff following surgery is postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV), and is a major concern for patients about surgery and anesthesia. In general, postoperative nausea and vomiting occur in 20 to 30% of patients who undergo surgery, although there are many differences in the values reported in different studies [1, 2].

Today, based on the results of extensive studies, a clear guideline has been published on how to administer PONV, according to which the prophylactic administration of antimycotic drugs is recommended for patients at moderate and high risk. The antimicrobial drugs used inhibit one or more neurotransmitter regions in the chemoreceptor trigger zone in the medulla and include anticholinergics, antipopaminergics, antihistaminergics, and antiserotonergics [3, 4].

Because at present in our country there is no specific protocol for how to administer PONV, and considering that the routine method of anesthesia is the use of general anesthesia with inhaled drugs with nitric oxide (NO) as well as opioids as Routine analgesics are used to control pain in surgical patients [5]; patients are at moderate to high risk for PONV (regardless of patient-related risk factors and surgery). As a result, prophylactic treatment for these patients is indicated, according to a guideline published by the American Society of Anesthesiologists [6].

The aim of this study was to determine the effect of ondansetron and metoclopramide on the prevention of PONV in high-risk patients. The reason for choosing these two drugs is that ondansetron is a drug that is widely used in the world today as a first-line drug in the prevention and treatment of PONV, and metoclopramide is a drug that is cheap and available as a common anti-emetic drug by surgeons PONV control is prescribed in Iran.

Materials and Methods

In this interventional study, 126 patients in Class 1 and 2 of the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA I-II) aged 18 to 65 years underwent coronary artery bypass graft surgery and received opioid medications during surgery, from 2018 to 2019, were examined in the surgical ward of Shahid Madani Hospital. Patients who have contraindications to the use of ondansetron or metoclopramide, have a history of taking drugs that interact with ondansetron or metoclopramide, a history of allergy to ondansetron or metoclopramide pregnant and lactating women and patients who have a mechanical cause for postoperative nausea and vomiting (such as premature obstruction or ileus) were excluded from the study.

The patients were visited by a respected anesthesiologist the day before surgery and are included in the study if they meet the criteria for selecting a research sample. The studied patients are completely randomly divided into 2 equal groups of 63 patients (using a table of random numbers by computer).

In the operating room, general anesthesia is induced with a standard dose of inhaled anesthetic and maintained with NO. It is prescribed as an intraoperative analgesic for the opioid patient. The desired anti-nausea drugs (ondansetron 4mg or metoclopramide) 10mg are taken by the anesthesiologist in the required number in equal volumes into the syringe and are prepared according to the patient's number to the anesthesiologist, who does not know the type of drug, and The drug is injected intravenously about 30 minutes before surgery or immediately after induction of anesthesia if the duration of surgery is less than half an hour. The PACU is cared for and then transferred to the general surgery ward. In order to control the confounding variables, all patients should be restricted to receiving food orally for at least 8 hours before to 24 hours after surgery and also be sufficiently hydrated and receive opioid analgesics if pain persists after surgery. Absolute rest for at least 24 hours after surgery. The patients were visited 24 hours after the surgery by the relevant intern, who did not know the patient's medication, and the patient questionnaire form was based on information obtained from patients and their companions, as well as the nurses' report, which The patient file will be registered and completed. The patients to be admitted to the study were visited by a respected anesthesiologist the day before surgery, and if they met the criteria for selecting the research sample, they were provided with complete and necessary explanations on how to perform the study and then written consent. It was taken from them.

After confirmation of this research in the ethics committee of Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, the objectives of the research were explained to patients in simple language. Written informed consent was completed by patients.

In the analysis of qualitative variables from Chi-Square statistical tests (Chi-Square) and Fisher Exact test (Fisher Exact test) and in the analysis of quantitative variables from t-test and non-parametric alternative tests suitable when needed using Spss and Statistica statistical software were used.

Findings

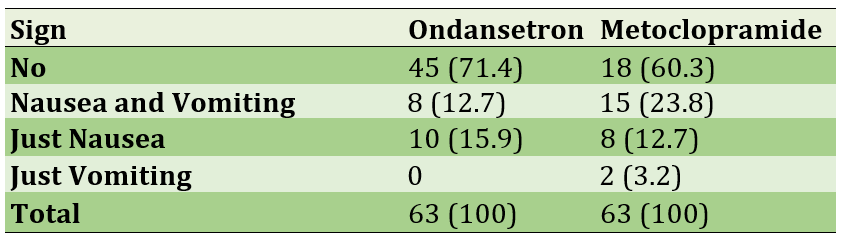

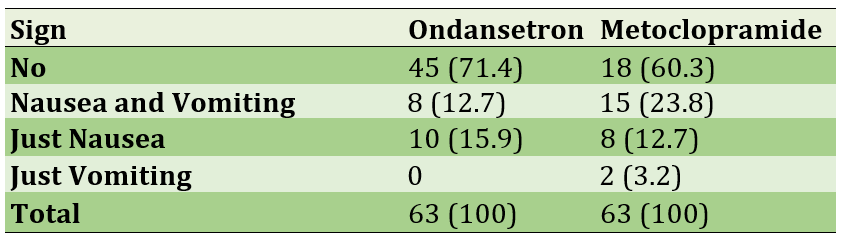

The rate of nausea in patients was about 67.5% with an average of 158.5 seconds of nausea in these patients each day and there was no significant difference between the two drug groups in terms of these two variables (p=0.342; p=0.900). The average rate of vomiting in patients was 19.8%, of which 52% had vomiting once and 48% had vomited more than once. There was a significant difference in the presence of vomiting in the two drug groups (p=0.044) but no significant difference was observed in the number of vomiting (p=0.097; Table 1).

Table 1) Frequency of the nausea and vomiting in participants

Discussion

The etiology of postoperative nausea and vomiting following open abdominal surgery depends on several factors, including patient-related factors, factors related to anesthesia technique, factors related to the type of surgery, and factors after surgery [7]. Because at present in our country there is no specific protocol for how to manage nausea and vomiting after surgery, and considering that the routine method of anesthesia is the use of general anesthesia with inhaled drugs and also opioid drugs as a routine analgesic Used to control pain in surgical patients, patients are at moderate to high risk for nausea and vomiting after surgery (regardless of patient-related risk factors and surgery) [8]. As a result, prophylactic treatment for these patients is indicated, according to a guideline published by the American Society of Anesthesiologists [9, 10]. Therefore, we decided to compare the effects of ondansetron and metoclopramide in the prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting in a present study [11, 12]. The present study is a prospective study that investigated the effect of ondansetron and metoclopramide on the prevention of nausea and vomiting after coronary artery bypass graft surgery. In this study, 126 patients in two groups of 63 were studied [13].

The results of this study showed that there was no significant difference between the two drug groups in terms of nausea in the first 24 hours after open abdominal surgery in patients receiving ondansetron 30 minutes before the end of surgery compared to metoclopramide. However, the incidence of vomiting during this period was lower in patients receiving ondansetron than in metoclopramide, and there was a significant difference between the two drug groups in terms of vomiting. In general, there is no significant difference between the two drug groups in terms of nausea and vomiting [14, 15].

In a recent study, both groups were similar in terms of risk factors for nausea and vomiting after surgery and there was a significant difference between the two drug groups in terms of most patient-related risk factors (sex, history of motion sickness, history of chronic nausea and vomiting, history). Nausea and vomiting in previous surgeries and smoking) and the type of surgery is not observed. In addition, the technique of induction and maintenance of anesthesia and the method of analgesic use during surgery were the same for all patients and all patients had the same conditions in terms of postoperative factors. As a result, the difference in the incidence of postoperative nausea and vomiting is mainly due to prophylactic antiemetic drugs prescribed during surgery [1, 16].

Because the side effects of ondansetron and metoclopramide are short-lived and self-limiting, the side effects of the prescribed anti-nausea drugs were not evaluated in this study. In general, the results of our study show that the two drugs ondansetron at a dose of 4 mg and metoclopramide at a dose of 10 mg in case of intravenous injection 30 minutes before surgery do not have a superior advantage over each other in preventing nausea and vomiting after surgery. Because metoclopramide is more economical than ondansetron, its use is recommended to prevent postoperative nausea and vomiting in high-risk patients [12, 14]. It is suggested that other studies with a larger sample size be performed in the future to confirm the accuracy of the results obtained from this study. In addition, in these trials, it is better to carefully control all the factors that may affect the outcome of the work (type of surgery, anesthesia technique and facto-release after surgery) and to be extremely careful in selecting patients. Another important point is the dose and time of injection of anti-nausea drugs, which should be adjusted according to the half-life and peak time of the drug.

Conclusion

Metoclopramide and Ondansetron have the similar effects on nausea and vomiting after coronary artery bypass graft surgery.

Acknowledgements: None declared by the authors.

Ethical Permission: This research was approved in the Ethics Committee of Tabriz University of Medical Sciences (IR.TBZMED.REC.1399.980).

Conflicts of Interests: None declared by the authors.

Funding/Support: None declared by the authors.

One of the major problems for patients and medical staff following surgery is postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV), and is a major concern for patients about surgery and anesthesia. In general, postoperative nausea and vomiting occur in 20 to 30% of patients who undergo surgery, although there are many differences in the values reported in different studies [1, 2].

Today, based on the results of extensive studies, a clear guideline has been published on how to administer PONV, according to which the prophylactic administration of antimycotic drugs is recommended for patients at moderate and high risk. The antimicrobial drugs used inhibit one or more neurotransmitter regions in the chemoreceptor trigger zone in the medulla and include anticholinergics, antipopaminergics, antihistaminergics, and antiserotonergics [3, 4].

Because at present in our country there is no specific protocol for how to administer PONV, and considering that the routine method of anesthesia is the use of general anesthesia with inhaled drugs with nitric oxide (NO) as well as opioids as Routine analgesics are used to control pain in surgical patients [5]; patients are at moderate to high risk for PONV (regardless of patient-related risk factors and surgery). As a result, prophylactic treatment for these patients is indicated, according to a guideline published by the American Society of Anesthesiologists [6].

The aim of this study was to determine the effect of ondansetron and metoclopramide on the prevention of PONV in high-risk patients. The reason for choosing these two drugs is that ondansetron is a drug that is widely used in the world today as a first-line drug in the prevention and treatment of PONV, and metoclopramide is a drug that is cheap and available as a common anti-emetic drug by surgeons PONV control is prescribed in Iran.

Materials and Methods

In this interventional study, 126 patients in Class 1 and 2 of the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA I-II) aged 18 to 65 years underwent coronary artery bypass graft surgery and received opioid medications during surgery, from 2018 to 2019, were examined in the surgical ward of Shahid Madani Hospital. Patients who have contraindications to the use of ondansetron or metoclopramide, have a history of taking drugs that interact with ondansetron or metoclopramide, a history of allergy to ondansetron or metoclopramide pregnant and lactating women and patients who have a mechanical cause for postoperative nausea and vomiting (such as premature obstruction or ileus) were excluded from the study.

The patients were visited by a respected anesthesiologist the day before surgery and are included in the study if they meet the criteria for selecting a research sample. The studied patients are completely randomly divided into 2 equal groups of 63 patients (using a table of random numbers by computer).

In the operating room, general anesthesia is induced with a standard dose of inhaled anesthetic and maintained with NO. It is prescribed as an intraoperative analgesic for the opioid patient. The desired anti-nausea drugs (ondansetron 4mg or metoclopramide) 10mg are taken by the anesthesiologist in the required number in equal volumes into the syringe and are prepared according to the patient's number to the anesthesiologist, who does not know the type of drug, and The drug is injected intravenously about 30 minutes before surgery or immediately after induction of anesthesia if the duration of surgery is less than half an hour. The PACU is cared for and then transferred to the general surgery ward. In order to control the confounding variables, all patients should be restricted to receiving food orally for at least 8 hours before to 24 hours after surgery and also be sufficiently hydrated and receive opioid analgesics if pain persists after surgery. Absolute rest for at least 24 hours after surgery. The patients were visited 24 hours after the surgery by the relevant intern, who did not know the patient's medication, and the patient questionnaire form was based on information obtained from patients and their companions, as well as the nurses' report, which The patient file will be registered and completed. The patients to be admitted to the study were visited by a respected anesthesiologist the day before surgery, and if they met the criteria for selecting the research sample, they were provided with complete and necessary explanations on how to perform the study and then written consent. It was taken from them.

After confirmation of this research in the ethics committee of Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, the objectives of the research were explained to patients in simple language. Written informed consent was completed by patients.

In the analysis of qualitative variables from Chi-Square statistical tests (Chi-Square) and Fisher Exact test (Fisher Exact test) and in the analysis of quantitative variables from t-test and non-parametric alternative tests suitable when needed using Spss and Statistica statistical software were used.

Findings

The rate of nausea in patients was about 67.5% with an average of 158.5 seconds of nausea in these patients each day and there was no significant difference between the two drug groups in terms of these two variables (p=0.342; p=0.900). The average rate of vomiting in patients was 19.8%, of which 52% had vomiting once and 48% had vomited more than once. There was a significant difference in the presence of vomiting in the two drug groups (p=0.044) but no significant difference was observed in the number of vomiting (p=0.097; Table 1).

Table 1) Frequency of the nausea and vomiting in participants

Discussion

The etiology of postoperative nausea and vomiting following open abdominal surgery depends on several factors, including patient-related factors, factors related to anesthesia technique, factors related to the type of surgery, and factors after surgery [7]. Because at present in our country there is no specific protocol for how to manage nausea and vomiting after surgery, and considering that the routine method of anesthesia is the use of general anesthesia with inhaled drugs and also opioid drugs as a routine analgesic Used to control pain in surgical patients, patients are at moderate to high risk for nausea and vomiting after surgery (regardless of patient-related risk factors and surgery) [8]. As a result, prophylactic treatment for these patients is indicated, according to a guideline published by the American Society of Anesthesiologists [9, 10]. Therefore, we decided to compare the effects of ondansetron and metoclopramide in the prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting in a present study [11, 12]. The present study is a prospective study that investigated the effect of ondansetron and metoclopramide on the prevention of nausea and vomiting after coronary artery bypass graft surgery. In this study, 126 patients in two groups of 63 were studied [13].

The results of this study showed that there was no significant difference between the two drug groups in terms of nausea in the first 24 hours after open abdominal surgery in patients receiving ondansetron 30 minutes before the end of surgery compared to metoclopramide. However, the incidence of vomiting during this period was lower in patients receiving ondansetron than in metoclopramide, and there was a significant difference between the two drug groups in terms of vomiting. In general, there is no significant difference between the two drug groups in terms of nausea and vomiting [14, 15].

In a recent study, both groups were similar in terms of risk factors for nausea and vomiting after surgery and there was a significant difference between the two drug groups in terms of most patient-related risk factors (sex, history of motion sickness, history of chronic nausea and vomiting, history). Nausea and vomiting in previous surgeries and smoking) and the type of surgery is not observed. In addition, the technique of induction and maintenance of anesthesia and the method of analgesic use during surgery were the same for all patients and all patients had the same conditions in terms of postoperative factors. As a result, the difference in the incidence of postoperative nausea and vomiting is mainly due to prophylactic antiemetic drugs prescribed during surgery [1, 16].

Because the side effects of ondansetron and metoclopramide are short-lived and self-limiting, the side effects of the prescribed anti-nausea drugs were not evaluated in this study. In general, the results of our study show that the two drugs ondansetron at a dose of 4 mg and metoclopramide at a dose of 10 mg in case of intravenous injection 30 minutes before surgery do not have a superior advantage over each other in preventing nausea and vomiting after surgery. Because metoclopramide is more economical than ondansetron, its use is recommended to prevent postoperative nausea and vomiting in high-risk patients [12, 14]. It is suggested that other studies with a larger sample size be performed in the future to confirm the accuracy of the results obtained from this study. In addition, in these trials, it is better to carefully control all the factors that may affect the outcome of the work (type of surgery, anesthesia technique and facto-release after surgery) and to be extremely careful in selecting patients. Another important point is the dose and time of injection of anti-nausea drugs, which should be adjusted according to the half-life and peak time of the drug.

Conclusion

Metoclopramide and Ondansetron have the similar effects on nausea and vomiting after coronary artery bypass graft surgery.

Acknowledgements: None declared by the authors.

Ethical Permission: This research was approved in the Ethics Committee of Tabriz University of Medical Sciences (IR.TBZMED.REC.1399.980).

Conflicts of Interests: None declared by the authors.

Funding/Support: None declared by the authors.

References

1. Pitts SR. Neither ondansetron nor metoclopramide reduced nausea and vomiting in the emergency department. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161:JC3. [Link] [DOI:10.7326/0003-4819-161-12-201412160-02003]

2. Talebpour M, Ghiasnejad Omrani N, Imani F, Shariat Moharari R, Pourfakhr P, Khajavi MR. Comparison effect of promethazine/dexamethasone and metoclopramide /dexamethasone on postoperative nausea and vomiting after laparascopic gastric placation: a randomized clinical trial. Anesth Pain Med. 2017;7:e57810. [Link] [DOI:10.5812/aapm.57810]

3. Maitra S, Som A, Baidya DK, Bhattacharjee S. Comparison of ondansetron and dexamethasone for prophylaxis of postoperative nausea and vomiting in patients undergoing laparoscopic surgeries: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Anesthesiol Res Pract. 2016;2016:7089454. [Link] [DOI:10.1155/2016/7089454]

4. Dalhat S, Mohammad A. Comparison of ondansetron and metoclopramide for the prevention of post-operative nausea and vomiting in day-case gynaecological laparoscopic surgeries. Niger J Basic Clin Sci. 2018;15(1):24-8. [Link] [DOI:10.4103/njbcs.njbcs_15_17]

5. Reza A, Riahi E, Daneshi A, Golchini E. The incidence of traumatic brain injury in Tehran, Iran. Brain Inj. 2018;32(4):487-92. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/02699052.2018.1429658]

6. Balakrishnan B, Rus RM, Chan KH, Martin AG, Awang MS. Prevalence of postconcussion syndrome after mild traumatic brain injury in young adults from a single neurosurgical center in east coast of Malaysia. Asian J Neurosurg. 2019:14(1):201-5. [Link] [DOI:10.4103/ajns.AJNS_49_18]

7. Bagheri-Hariri S, Bahreini M, Farshidmehr P, Barazandeh S, Babaniamansour S, Aliniagerdroudbari E, et al. The effect of extended-focused assessment with sonography in trauma results on clinical judgment accuracy of the physicians managing patients with blunt thoracoabdominal trauma. Arch Trauma Res. 2019;8(4):207-13. [Link] [DOI:10.4103/atr.atr_57_19]

8. Farzaneh E, Fattahzadeh-Ardalani G, Abbasi V, Kahnamouei-aghdam F, Molaei B, Iziy E, et al. The epidemiology of hospital-referred head injury in Ardabil city. Emerg Med Int. 2017;2017:1439486. [Link] [DOI:10.1155/2017/1439486]

9. Gerritsen H, Samim M, Peters H, Schers H, van de Laar FA. Incidence, course and risk factors of head injury: A retrospective cohort study. BMJ Open. 2018;8(5):e020364. [Link] [DOI:10.1136/bmjopen-2017-020364]

10. Zamani M, Namdar B, Azizkhani R, Ahmadi O, Esmailian M. Comparing the antiemetic effects of ondansetron and metoclopramide in patients with minor head trauma. Emergency. 2015;3(4):137-40. [Link]

11. Hashimoto H, Abe M, Tokyama O, Mizutani H, Uchitomi Y, Yamaguchi T, et al. Olanzapine 5 mg plus standard antiemetic therapy for the prevention of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (J-FORCE): a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2020:21(2):242-9. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30678-3]

12. Ithimakin S, Theeratrakul P, Laocharoenkiat A, Nimmannit A, Akewanlop C, Soparattanapaisarn N, et al. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of aprepitant versus two dosages of olanzapine with ondansetron plus dexamethasone for prevention of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting in patients receiving high-emetogenic chemotherapy. Support Care Cancer. 2020;28:5335-42. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s00520-020-05380-6]

13. Jeon SY, Han HS, Bae WK, Park MR, Shim H, Lee SC, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of the safety and efficacy of olanzapine for the prevention of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting in patients receiving moderately emetogenic chemotherapy: results of the korean south west oncology group (KSWOG) study . Cancer Res Treat. 2019;51:90-7. [Link] [DOI:10.4143/crt.2017.577]

14. Mukhopadhyay S, Kwatra KPA, Badyal D. Role of olanzapine in chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting on platinum-based chemotherapy patients: A randomized controlled study. Support Care Cancer. 2017;25:145-54. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s00520-016-3386-9]

15. Tienchaiananda P, Nipondhkit W, Maneenil K, Sa-Nguansai S, Payapwattanawong S, SLaohavinij S, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study evaluating the efficacy of combination olanzapine, ondansetron and dexamethasone for prevention of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting in patients receiving doxorubicin plus cyclophosphamide. Ann Palliat Med. 2019;8:372-80. [Link] [DOI:10.21037/apm.2019.08.04]

16. Navari RM, Pywell CM, Le-Rademacher JG, White P,. Dodge AB, Albany C, et al. Olanzapine for the Treatment of Advanced Cancer-Related Chronic Nausea and/or Vomiting. JAMA Oncol. 2020;6:895-9. [Link] [DOI:10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.1052]

17. Kalakonda N, Maerevoet M, Cavallo F, Follows G, Goy A, Vermaat JS, et al. Selinexor in patients with relapsed or refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (SADAL): a single-arm, multinational, multicentre, open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet Haematol. 2020;7:e511-e522. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/S2352-3026(20)30120-4]

18. Chari A, Vogl DT, Gavriatopoulou M, Nooka AK, Yee AJ, Huff CA, et al. Oral selinexor-dexamethasone for triple-class refractory multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2019;38(8):727-38. [Link] [DOI:10.1056/NEJMoa1903455]