GMJ Medicine

eISSN : 2626-3041

Volume 2, Issue 4 (2023)

GMJM 2023, 2(4): 115-118 |

Back to browse issues page

Article Type:

Subject:

History

Received: 2023/04/11 | Accepted: 2023/09/20 | Published: 2023/11/9

Received: 2023/04/11 | Accepted: 2023/09/20 | Published: 2023/11/9

How to cite this article

Mahdavi F, Eghdam Zamiri R. The Incidence and Risk Factors of Surgical Wound Infection after Abdominal Hysterectomy in Cancerous Women. GMJM 2023; 2 (4) :115-118

URL: http://gmedicine.de/article-2-210-en.html

URL: http://gmedicine.de/article-2-210-en.html

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Rights and permissions

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Authors

F. Mahdavi1, R. Eghdam Zamiri *1

1- Tuberculosis and Lung Disease Research Center, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran

Keywords:

| Abstract (HTML) (1462 Views)

Full-Text: (433 Views)

Introduction

Infections are an important cause of morbidity in the postoperative period and surgical wound infection is one of the most important types of these infections [1]. Hysterectomy is one of the most common gynecological surgeries after cesarean section and infection of various sites including wound infection [2], vaginal floor infection and urinary tract infection are complications after hysterectomy. This complication can lead to long hospital stay, reoperation and repeated manipulations [3]. The rate of infection after abdominal hysterectomy is reported to be approximately 15 to 24%, which is reduced to about 10% with prophylactic antibiotics [4].

In one study, patients undergoing abdominal hysterectomy receiving antibiotic prophylaxis developed urinary tract infection, wound infection, fever of unknown cause, vaginal infection, and intra-abdominal infection [5]. In another study, the incidence of wound infection after abdominal hysterectomy was reported to be about 5% and the risk factors for inadequate antibiotic prophylaxis and obesity were raised [6]. In another study, 8% of abdominal hysterectomies developed abdominal wall infections, with most patients receiving prophylactic antibiotics [7, 8] . Obesity studies have identified a risk factor for infection after abdominal hysterectomy [7].

Hysterectomy is the most common surgery of choice after cesarean section in medical centers [9], and abdominal wall infection is one of the most important complications after this operation, which leads to readmission of the patient and long-term treatments. Therefore, this study was performed to determine the incidence and risk factors of surgical wound infection after abdominal hysterectomy in women with and without cancer.

Materials and Methods

Cases of wound infection based on the criteria for removing purulent discharge from a newly closed surgical wound with or without opening the wound and fever, positive culture of the discharge from the surgical site, or the surgeon's diagnosis of surgical wound infection that needs to be reopened Had; Within 10 days after the operation, the patient was diagnosed and registered by referring to the clinic or ward.

Risk factors for diabetes, hypertension, preoperative prophylaxis, malignant pathology, corticosteroids, immunosuppressive drugs, body mass index more than 25kg/m2, shaving site more than one day before surgery, bath with The interval more than one day before the operation was more than one day in the preoperative hospital and the duration of the hysterectomy was more than 60 minutes.

Data were entered into the computer using SPSS 21. Data description was done by presenting frequency tables and describing qualitative characteristics through frequency and percentage and quantitative characteristics through means and amplitude of changes. Chi-square test was used to compare qualitative variables (two or more states) and t-test was used to compare quantitative variables. OR communication index and 95% confidence interval through logistic regression were used to determine the risk factors. The level of statistical significance in all tests was considered less than 0.05.

Findings

The mean age of patients participating in the study was 46.59±8.41 years with an age range of 17 to 81 years. Infection was observed in 26 patients (6.5%) within 10 days after surgery. The most common symptom of infection was fever (24 patients, 6%). In 16 patients, there was fever with discharge and redness at the surgical wound site. In 4 patients, fever occurred with discharge from the wound and partial opening of the surgical wound, and in 6 cases, there was extensive opening of the surgical wound with purulent discharge from the wound, which was repaired.

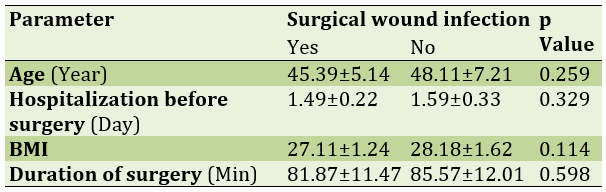

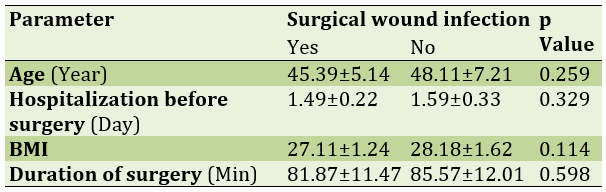

The mean age in the group with abdominal wall infection was 45.39±5.14 years and in the non-infected group was 48.11±7.21 years which was not statistically significant. There was no statistically significant difference between the days of preoperative hospitalization, body mass index and duration of surgery in patients with surgical wound infection and without infection (Table 1).

Table 1) Mean and standard deviation of parameters in wound hysterectomy

There was a history of corticosteroids in 14 patients and immunosuppressive drugs (azitoprine due to rheumatic disease) in 4 patients (1%). In one patient taking corticosteroids, a surgical wound infection occurred. Also, surgical wound infection occurred in 2 patients taking immunosuppressive drugs. These differences were not statistically significant. The surgical site was performed in 367 patients the day before surgery, in 20 patients two days before surgery and in 13 patients on the day of surgery.

Also, bathing was performed in 15 patients on the day of surgery in 370 patients the day before surgery in 12 patients two days before surgery and in 3 patients four days before surgery. All patients received cefazolin as prophylaxis; But combined prophylaxis with several antibiotics was received in only 4 patients. Clindamycin and gentamicin were prescribed half an hour before surgery.

Hysterectomy was performed in 373 complete patients and in 27 patients supraservically. Emergency hysterectomy was performed in 6 patients due to severe hemorrhage and in other patients it was performed selectively. The shortest duration of surgery was 45 minutes and the longest time of operation was 180 minutes.

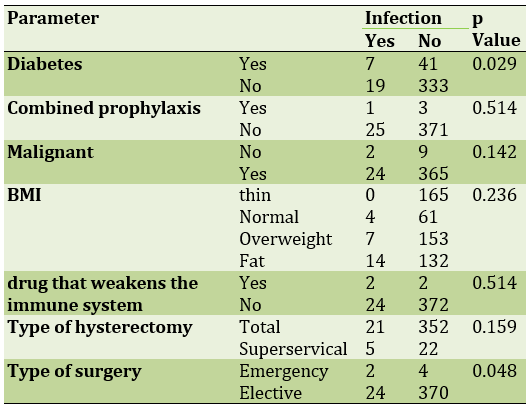

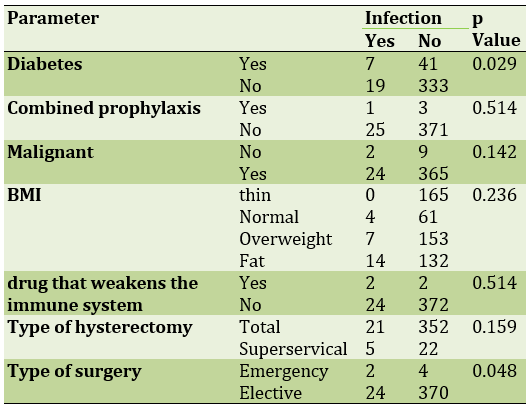

Pathology was reported in 11 malignant patients and in 389 benign patients. Cases of malignancy included 6 cases of ovarian epithelial cancer and 5 cases of endometrial cancer. The relationship between the variables of diabetes, combined prophylaxis, body mass index, type of hysterectomy and type of operation with the incidence of wound infection is shown in Table 2.

Table 2) PrevalenAce of studied parameters in infection with abdominal hysterectomy

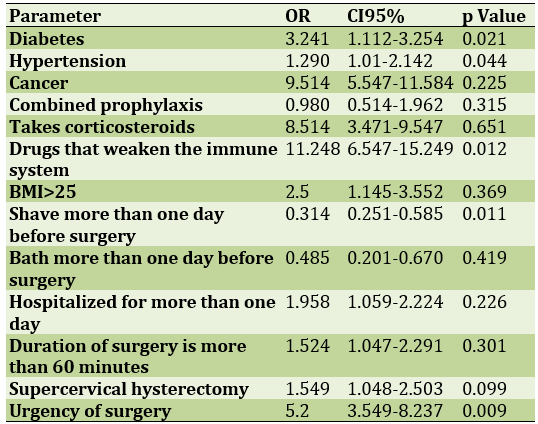

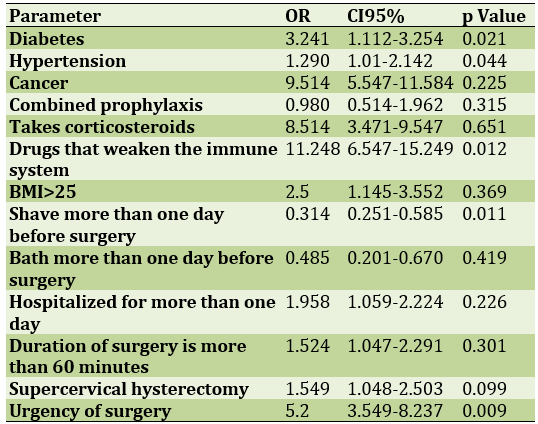

The use of drugs that weaken the immune system, the urgency of the operation and diabetes are the risk factors for wound infection after hysterectomy (Table 3).

Table 3) Determining the risk factors for wound infection after abdominal hysterectomy using regression analysis

Discussion

The results of this study showed that wound infection occurred after surgery in 6.5% of patients. Surgical wound infection after abdominal hysterectomy in several studies has been between 5 and 8%, which is consistent with the results of our study. Wound infection after surgery has a great impact on the patient's quality of life and significantly increases the cost of patient care. The result is increased pain, care for an infectious open wound, and even in the more complex stages of the patient's death. Some of the factors influencing the spread of wound infection include host resistance, surgical technique, number and type of organism present in the wound at the end of surgery. Many patients who are hospitalized for a long time or those who have an underlying disease have an increase in the number of organisms located in their skin. Therefore, choosing the appropriate method and antibiotic for the treatment of surgical infections requires accurate information about the occurrence of vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, common infectious flora, and their percentage of sensitivity to common antibiotics [10-12].

In our study, diabetes mellitus, immunosuppressive drugs, and the urgency of the operation were identified as risk factors for wound infection after hysterectomy. In most previous studies, the history of diseases and the use of drugs in the subjects have not been studied, however, the results of our studies are consistent with the results of other studies. In the present study, all patients received Keflin as prophylaxis. One study recommended that all patients who were candidates for vaginal hysterectomy should receive prophylactic antibiotics [13, 14].

In one study, factors related to wound infection, long-term hospitalization before emergency surgery, and long-term surgery were identified. However, in that study, apart from abdominal hysterectomy, other abdominal surgeries were also examined, which cannot be examined due to the difference in surgery time in different surgeries. In our study, almost all hysterectomies were performed within 60 to 120 minutes, and patients were admitted the day before surgery. Therefore, in terms of these variables, there are similarities with other studies [15-17].

In several other studies, severe blood transfusions and obesity were identified as risk factors for wound infection. Prolonged surgery and obesity were also associated with a higher risk of wound infection. This discrepancy may be related to the lack of severe obesity in our patients and the fact that most hysterectomies were performed in this study in less than two hours [18-20].

Conclusion

The rate of infection after abdominal hysterectomy is the same as in other studies; To reduce the rate of infection after abdominal hysterectomy, preventive measures should be taken based on the risk of infection.

Acknowledgements: None declared by the authors.

Ethical Permission: The present study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Tabriz University of Medical Sciences (IR.TBZMED.REC.1400.018).

Conflicts of Interests: None declared by the authors.

Funding/Support: None declared by the authors.

Infections are an important cause of morbidity in the postoperative period and surgical wound infection is one of the most important types of these infections [1]. Hysterectomy is one of the most common gynecological surgeries after cesarean section and infection of various sites including wound infection [2], vaginal floor infection and urinary tract infection are complications after hysterectomy. This complication can lead to long hospital stay, reoperation and repeated manipulations [3]. The rate of infection after abdominal hysterectomy is reported to be approximately 15 to 24%, which is reduced to about 10% with prophylactic antibiotics [4].

In one study, patients undergoing abdominal hysterectomy receiving antibiotic prophylaxis developed urinary tract infection, wound infection, fever of unknown cause, vaginal infection, and intra-abdominal infection [5]. In another study, the incidence of wound infection after abdominal hysterectomy was reported to be about 5% and the risk factors for inadequate antibiotic prophylaxis and obesity were raised [6]. In another study, 8% of abdominal hysterectomies developed abdominal wall infections, with most patients receiving prophylactic antibiotics [7, 8] . Obesity studies have identified a risk factor for infection after abdominal hysterectomy [7].

Hysterectomy is the most common surgery of choice after cesarean section in medical centers [9], and abdominal wall infection is one of the most important complications after this operation, which leads to readmission of the patient and long-term treatments. Therefore, this study was performed to determine the incidence and risk factors of surgical wound infection after abdominal hysterectomy in women with and without cancer.

Materials and Methods

Cases of wound infection based on the criteria for removing purulent discharge from a newly closed surgical wound with or without opening the wound and fever, positive culture of the discharge from the surgical site, or the surgeon's diagnosis of surgical wound infection that needs to be reopened Had; Within 10 days after the operation, the patient was diagnosed and registered by referring to the clinic or ward.

Risk factors for diabetes, hypertension, preoperative prophylaxis, malignant pathology, corticosteroids, immunosuppressive drugs, body mass index more than 25kg/m2, shaving site more than one day before surgery, bath with The interval more than one day before the operation was more than one day in the preoperative hospital and the duration of the hysterectomy was more than 60 minutes.

Data were entered into the computer using SPSS 21. Data description was done by presenting frequency tables and describing qualitative characteristics through frequency and percentage and quantitative characteristics through means and amplitude of changes. Chi-square test was used to compare qualitative variables (two or more states) and t-test was used to compare quantitative variables. OR communication index and 95% confidence interval through logistic regression were used to determine the risk factors. The level of statistical significance in all tests was considered less than 0.05.

Findings

The mean age of patients participating in the study was 46.59±8.41 years with an age range of 17 to 81 years. Infection was observed in 26 patients (6.5%) within 10 days after surgery. The most common symptom of infection was fever (24 patients, 6%). In 16 patients, there was fever with discharge and redness at the surgical wound site. In 4 patients, fever occurred with discharge from the wound and partial opening of the surgical wound, and in 6 cases, there was extensive opening of the surgical wound with purulent discharge from the wound, which was repaired.

The mean age in the group with abdominal wall infection was 45.39±5.14 years and in the non-infected group was 48.11±7.21 years which was not statistically significant. There was no statistically significant difference between the days of preoperative hospitalization, body mass index and duration of surgery in patients with surgical wound infection and without infection (Table 1).

Table 1) Mean and standard deviation of parameters in wound hysterectomy

There was a history of corticosteroids in 14 patients and immunosuppressive drugs (azitoprine due to rheumatic disease) in 4 patients (1%). In one patient taking corticosteroids, a surgical wound infection occurred. Also, surgical wound infection occurred in 2 patients taking immunosuppressive drugs. These differences were not statistically significant. The surgical site was performed in 367 patients the day before surgery, in 20 patients two days before surgery and in 13 patients on the day of surgery.

Also, bathing was performed in 15 patients on the day of surgery in 370 patients the day before surgery in 12 patients two days before surgery and in 3 patients four days before surgery. All patients received cefazolin as prophylaxis; But combined prophylaxis with several antibiotics was received in only 4 patients. Clindamycin and gentamicin were prescribed half an hour before surgery.

Hysterectomy was performed in 373 complete patients and in 27 patients supraservically. Emergency hysterectomy was performed in 6 patients due to severe hemorrhage and in other patients it was performed selectively. The shortest duration of surgery was 45 minutes and the longest time of operation was 180 minutes.

Pathology was reported in 11 malignant patients and in 389 benign patients. Cases of malignancy included 6 cases of ovarian epithelial cancer and 5 cases of endometrial cancer. The relationship between the variables of diabetes, combined prophylaxis, body mass index, type of hysterectomy and type of operation with the incidence of wound infection is shown in Table 2.

Table 2) PrevalenAce of studied parameters in infection with abdominal hysterectomy

The use of drugs that weaken the immune system, the urgency of the operation and diabetes are the risk factors for wound infection after hysterectomy (Table 3).

Table 3) Determining the risk factors for wound infection after abdominal hysterectomy using regression analysis

Discussion

The results of this study showed that wound infection occurred after surgery in 6.5% of patients. Surgical wound infection after abdominal hysterectomy in several studies has been between 5 and 8%, which is consistent with the results of our study. Wound infection after surgery has a great impact on the patient's quality of life and significantly increases the cost of patient care. The result is increased pain, care for an infectious open wound, and even in the more complex stages of the patient's death. Some of the factors influencing the spread of wound infection include host resistance, surgical technique, number and type of organism present in the wound at the end of surgery. Many patients who are hospitalized for a long time or those who have an underlying disease have an increase in the number of organisms located in their skin. Therefore, choosing the appropriate method and antibiotic for the treatment of surgical infections requires accurate information about the occurrence of vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, common infectious flora, and their percentage of sensitivity to common antibiotics [10-12].

In our study, diabetes mellitus, immunosuppressive drugs, and the urgency of the operation were identified as risk factors for wound infection after hysterectomy. In most previous studies, the history of diseases and the use of drugs in the subjects have not been studied, however, the results of our studies are consistent with the results of other studies. In the present study, all patients received Keflin as prophylaxis. One study recommended that all patients who were candidates for vaginal hysterectomy should receive prophylactic antibiotics [13, 14].

In one study, factors related to wound infection, long-term hospitalization before emergency surgery, and long-term surgery were identified. However, in that study, apart from abdominal hysterectomy, other abdominal surgeries were also examined, which cannot be examined due to the difference in surgery time in different surgeries. In our study, almost all hysterectomies were performed within 60 to 120 minutes, and patients were admitted the day before surgery. Therefore, in terms of these variables, there are similarities with other studies [15-17].

In several other studies, severe blood transfusions and obesity were identified as risk factors for wound infection. Prolonged surgery and obesity were also associated with a higher risk of wound infection. This discrepancy may be related to the lack of severe obesity in our patients and the fact that most hysterectomies were performed in this study in less than two hours [18-20].

Conclusion

The rate of infection after abdominal hysterectomy is the same as in other studies; To reduce the rate of infection after abdominal hysterectomy, preventive measures should be taken based on the risk of infection.

Acknowledgements: None declared by the authors.

Ethical Permission: The present study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Tabriz University of Medical Sciences (IR.TBZMED.REC.1400.018).

Conflicts of Interests: None declared by the authors.

Funding/Support: None declared by the authors.

References

1. Aghamohammadi D, Mehdinavaz Aghdam A, Khanbabayi Gol M. Prevalence of infections associated with port and predisposing factors in women with common cancers under chemotherapy referred to hospitals in Tabriz in 2015. IJOGI. 2019;21(11):7-13. [Persian] [Link]

2. Aghamohammadi D, Khanbabayi Gol M. Effect of intravenous infusion of magnesium sulfate on opioid use and hemodynamic status after hysterectomy: double-blind clinical trial. IJOGI. 2019;22(7):32-38. [Persian] [Link]

3. Surgical Site Infection (SSI) [Internet]. Georgia: CDC. 2010 Nov [cited 2021, 24 Feb]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/hai/ssi/ssi.html [Link]

4. Ban KA, Minei JP, Laronga C, Harbrecht BG, Jensen EH, Fry DE. American college of surgeons and surgical infection society: Surgical site infection guidelines, 2016 update. J Am Coll Surg. 2017;224(1):59-74. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2016.10.029]

5. Winfield RD, Reese S, Bochicchio K, Mazuski JE, Bochicchio GV. Obesity and the risk for surgical site infection in abdominal surgery. Am Surg. 2016;82(4):331-6. [Link] [DOI:10.1177/000313481608200418]

6. Pop-Vicas A, Musuuza JS, Schmitz M, Al-Niaimi A, Safdar N. Incidence and risk factors for surgical site infection post-hysterectomy in a tertiary care center. Am J Infect Control. 2017;45(3):284-7. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.ajic.2016.10.008]

7. Mazzeffi M, Tanaka K, Galvagno S. Red Blood Cell Transfusion and surgical site infection after colon resection surgery: A cohort study. Anesth Analg. 2017;125(4):1316-21. [Link] [DOI:10.1213/ANE.0000000000002099]

8. Webster J, Osborne S. Preoperative bathing or showering with skin antiseptics to prevent surgical site infection. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(2):CD004985. [Link] [DOI:10.1002/14651858.CD004985.pub5]

9. Edmiston Jr CE, Lee CJ, Krepel CJ, Spencer M, Leaper D, Brown KR, et al. Evidence for a standardized preadmission showering regimen to achieve maximal antiseptic skin surface concentrations of chlorhexidine gluconate, 4%, in surgical patients. JAMA Surg. 2015;150(11):1027-33. [Link] [DOI:10.1001/jamasurg.2015.2210]

10. Duggan EW, Carlson K, Umpierrez GE. Perioperative hyperglycemia management: An update. Anesthesiology. 2017;126(3):547-60. [Link] [DOI:10.1097/ALN.0000000000001515]

11. Berríos-Torres SI, Umscheid CA, Bratzler DW, Leas B, Stone EC, Kelz RR, et al. Centers for disease control and prevention guideline for the prevention of surgical site infection, 2017. JAMA Surg. 2017;152(8):784-91. [Link] [DOI:10.1001/jamasurg.2017.0904]

12. Sessler DI Perioperative thermoregulation and heat balance. Lancet. 2016;387(10038):2655-2664. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00981-2]

13. Hopf HW. Perioperative temperature management: time for a new standard of care?. Anesthesiology. 2015;122(2):229-30. [Link] [DOI:10.1097/ALN.0000000000000552]

14. Dumville JC, Gray TA, Walter CJ, Sharp CA, Page T, Macefield R, et al. Dressings for the prevention of surgical site infection. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;12(12):CD003091. [Link] [DOI:10.1002/14651858.CD003091.pub4]

15. Echebiri NC, McDoom MM, Aalto MM, Fauntleroy J, Nagappan N, Barnabei VM. Prophylactic use of negative pressure wound therapy after cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125(2):299-307. [Link] [DOI:10.1097/AOG.0000000000000634]

16. Webster J, Liu Z, Norman G, Dumville JC, Chiverton L, Scuffham P, et al. Negative pressure wound therapy for surgical wounds healing by primary closure. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;3(3):CD009261. [Link] [DOI:10.1002/14651858.CD009261.pub4]

17. Tartari E, Weterings V, Gastmeier P, Baño JR. Patient engagement with surgical site infection prevention: An expert panel perspective. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2017;6(1):1-10. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s13756-017-0202-3]

18. Anderson PA, Savage JW, Vaccaro AP, Radcliff K, Arnold PM, Lawrence BD, et al. Prevention of surgical site infection in spine surgery. Neurosurgery. 2017;80(3S):S114-S123. [Link] [DOI:10.1093/neuros/nyw066]

19. Pellegrini JE, Toledo P, Soper DE, Bradford WC, Cruz DA, et al. consensus bundle on prevention of surgical site infections after major gynecologic surgery. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;129(1):50-61. [Link] [DOI:10.1097/AOG.0000000000001751]

20. Khanbabayi Gol M. An investigation into the effects of magnesium sulfate on the complications of succinylcholine administration in nulliparous women undergoing elective cesarean section: A double-blind clinical trial. Int J Women Health Reprod Sci. 2019;7(4):520-5. [Link] [DOI:10.15296/ijwhr.2019.86]