GMJ Medicine

eISSN : 2626-3041

Volume 3, Issue 1 (2024)

GMJM 2024, 3(1): 13-17 |

Back to browse issues page

Article Type:

Subject:

History

Received: 2023/07/18 | Accepted: 2023/12/29 | Published: 2024/02/25

Received: 2023/07/18 | Accepted: 2023/12/29 | Published: 2024/02/25

How to cite this article

Mohammad Alizade F, Ghaffari M, Khodakarim S, Ramezankhani A. Effect of a Health Belief Model Educational Intervention on Promoting Fistula Care Behaviors in Hemodialysis Patients. GMJM 2024; 3 (1) :13-17

URL: http://gmedicine.de/article-2-217-en.html

URL: http://gmedicine.de/article-2-217-en.html

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Rights and permissions

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

1- Faculty of Health, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

2- Health Department, Faculty of Health, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

3- Epidemiology Department, Faculty of Health, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

2- Health Department, Faculty of Health, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

3- Epidemiology Department, Faculty of Health, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

Keywords:

| Abstract (HTML) (1438 Views)

Full-Text: (480 Views)

Introduction

The kidneys regulate body fluids, electrolytes, and acid-base balance [1]. Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is increasing worldwide and is a public problem for worldwide health [2]. Kidney diseases affect over 750 million people worldwide [3].

The CKD has a 5–15% global prevalence worldwide [4]. The burden, detection, and treatment of kidney diseases vary in different countries. The magnitude and effect of kidney diseases are efficiently defined in developed and developing countries [5]. CKD is associated with raised progression to end-stage renal disease and reduced survival. Faulted renal function increases excretion products of the kidneys in the blood and leads to terminal CKD [6]. Patients with terminal CKD need replacement treatments. World Kidney Day 2019 suggests an opportunity to increase awareness of kidney diseases and suggests considering its burden and current state for prevention and management. Hemodialysis, peritoneal dialysis, and kidney transplantation are commonly used to treat CKD [6]. Hemodialysis is a replacement treatment in which a dialyzer removes blood toxins, nitrogenous wastes, and excess water from the blood and returns clear blood to the body [7]. Hemodialysis commonly lasted 4 hours and 3 times per week [8]. The patients need an arteriovenous fistula for conducting hemodialysis [6]. An arteriovenous fistula is an appropriate vascular access for the hemodialysis method because it has longer survival and low rates of complications [9]. However, arteriovenous fistula needs management and self-care before, during, and after hemodialysis [6]. It must be considered an antiseptic solution before the hemodialysis. To maintain the best conditions for hemodialysis, patients must be aware of self-care behaviors associated with arteriovenous fistula [10]. Patients must be educated about the association of arteriovenous fistula because it can help increase the number of patients who perform hemodialysis using a fistula [11, 12]. Self-care is commonly obtained in patients with enough information associated with fistula [12]. Self-care with arteriovenous fistula has a long history, and several studies have investigated it [6, 13, 14], but the health belief model (HBM) has not been investigated.

The HBM was developed to explain behaviors associated with tuberculosis screening during the 1950s. It comprises concepts that help patients prevent, screen, and control illness conditions. It includes susceptibility, severity, benefits, barriers to a behavior, cues to action, and self-efficacy [15]. Perceived susceptibility and severity are defined as a feeling of patients from threats created by their current behavioral patterns [16]. Perceived benefit is patients’ beliefs that change their behavior to have more benefits [16]. Perceived belief is defined as the tangible and psychological costs of the advised action [16]. Self-efficacy is patients’ feeling for overcoming perceived barriers [16].

Education based on HBM may help hemodialysis patients promote fistula care behaviors, but no study has investigated this. The present study investigated the effect of education based on HBM on promoting fistula care behaviors of hemodialysis patients.

Materials and Methods

Study design

The present study was an experimental and interventional study in dialysis units of different hospitals and in patients who used arteriovenous fistula for hemodialysis.

Population and sampling

This study was performed in dialysis units of hospitals affiliated with Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences. The criteria for participants to be eligible for the study were willingness to participate in the research, an arteriovenous fistula more than 6 months old on hemodialysis, performing dialysis three times a week, and having the ability to read and write. The exclusion criteria were patient mortality, unwillingness to participate, patient transfer to another section for dialysis, and having a transplant. The target population included hemodialytic patients referred to Shahid Modares, Ayatollah Taliqani, and Imam Hussain hospitals. Thirty-five patients referred to the dialysis center of Shahid Modares Hospital (n=22) and Taliqani Hospital (n=13) were selected as the intervention group, and 35 patients referred to Imam Hussain Hospital were selected as a control group.

Data collection and instrument

The data were collected from January to March 2018. The information for demographic characteristics (age, gender, education, and marital status) and clinical characteristics (dialysis period, history of hypertension, diabetes, and renal diseases) were collected by using a questionnaire designed by the authors. Information concerning awareness of self-care behaviors for hemodialysis was collected by a questionnaire designed by the authors, which included 2 questions at the 3-level and 4-level levels. A questionnaire was designed by the authors for the HBM and included variables of perceived susceptibility (2 items), perceived severity (2 items), perceived benefits (2 items), barriers (3 items), and self-efficacy (4 items). Responses were designed based on a Likert scale with five possible answers, and higher scores indicated patients’ higher frequency of variables.

Face and content validities were used to validate the questionnaires. Content validity (CVI) is a common approach for investigating content validity in instrument development. The content validity ratio (CVR) investigates the essentials of an item. To investigate the validities of CVI and CVR of the questionnaire, 10 experienced experts investigated the questionnaires and presented comments for improving the questionnaire. The comments were used, and the questionnaires were revised. To test the instrument's reliability, the questionnaire was distributed among 30 hemodialytic patients in Shohadaye Tajrish Hospital that had not been studied in the current study. Cronbach’s alpha values were 0.741, 0.760, 0.766, 0.71, 0.789, 0.776, and 0.779 for fistula care behaviors, awareness, perceived susceptibility, perceived severity, perceived benefits, perceived barriers, and self-efficacy. Values of 0.70 and higher show the reliability of the questionnaire. The questionnaires had a reliability of 0.7, and they are reliable.

Intervention

The self-made questionnaire was distributed between the control and intervention groups before interventions (pre-test) and during dialysis. Educational contents were prepared based on the pre-test. With regards to the condition and situation of patients during dialysis, the educational intervention was performed for the intervention group using personal consultation (face to face) and, in some cases, consultation sessions in pairs or triads that were followed by Q & As. All the interventions were conducted based on HBM constructs and self-care purposes. An educational session was held for 15-20 minutes, and fistula care behaviors were discussed. Instructional media, such as a guide to using fistula for hemodialytic patients, were also used. The questionnaires were collected from the same patients in Modarres and Taliqani hospitals immediately and 2 months later.

Data analysis

To analyze the effect of education on promoting hemodialytic patients’ self-care behaviors, the Chi-squared and independent-sample t-test were used by SPSS 16 software, and a repeated measure test was also used. A p<0.05 was considered as significant.

Findings

Most patients had an age mean of 55–65 years (31.4%) and 65 and 75 years (40%) in the intervention and control groups, respectively. There was no significant difference in age, gender, marital status, blood pressure, and diabetes (p>0.05). Significant differences between the groups were found for education, kidney disease history, and dialysis period (p<0.05).

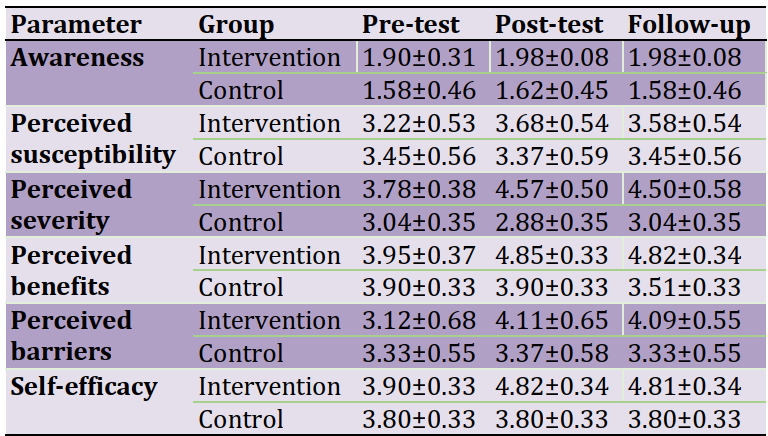

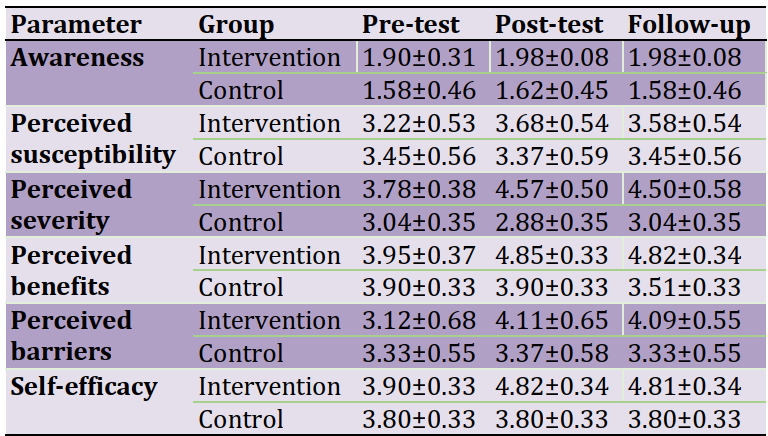

The awareness score did not significantly differ between the intervention and control groups in the pre-test, post-test, and follow-up (p=0.06). The results showed significant interaction effects between time and group for the perceived susceptibility (p=0.001). The results showed decreased scores in the intervention group, but it was significantly higher in the intervention group compared to the control group (p<0.05). It can be implicated that educational interventions significantly improved the perceived susceptibility (p=0.001). The score for perceived severity was lower in the control group compared to the intervention group in the pre-test. The repeated-measure test showed that the perceived severity score of fistula care behavior was significantly higher in the intervention group compared to the control group (p<0.05), immediately and after 2 months. It means that the intervention significantly improved the perceived severity. A significant interaction between group and time was observed (p=0.001) for the perceived severity. It means that educational interventions could increase the perceived severity, which was significantly higher after 2 months. The results showed that educational intervention increased perceived benefits immediately and after 2 months (p<0.05). It means that educational intervention still improved perceived benefits after 2 months. It was observed that a significant interaction between time and group for perceived benefits (p=0.001). The intervention increased the perceived benefits. Similar to previous parts, the educational interventions perceived barriers. The results showed that the perceived barriers were significantly higher after the educational interventions (p<0.05). It means that the score for the perceived barriers was the same but increased from the pre-test to the post-test in the intervention group (p<0.05). The results showed that self-efficacy was significantly higher in the intervention group compared to the control group after educational interventions. The results showed that scores were 3.80 in all the periods, but it was significantly increased in the intervention group immediately and after 2 months (p<0.05). A significant interaction between group and time was observed for self-efficacy (p=0.001; Table 1).

Table 1. The mean of awareness, susceptibility, severity, benefits, barriers, and self-efficacy scores of hemodialytic patients concerning fistula care behavior before, immediately, and 2 months after intervention in the groups

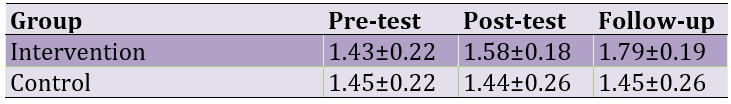

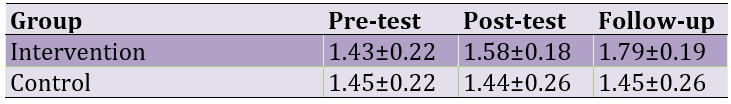

The educational intervention improved fistula-care behavior (p<0.05). The results showed that educational interventions significantly improved fistula-care behavior scores in post-test and follow-up (p=0.001). The score was specifically higher after 2 months. A significant interaction was observed between the group and time for fistula care behavior (p=0.001). The fistula care behavior was improved during the intervention groups (Table 2).

Table 2. The mean scores of fistula-care behavior in hemodialytic patients before, immediately, and 2 months after the educational intervention in groups

Discussion

The results showed that educational intervention did not have significant effects on awareness. Daniali et al. [17] showed that educational interventions significantly improved awareness in patients with multiple sclerosis. The difference between the findings of the present study and Daniali et al. is due to disease and intervention type. Other studies also showed that educational interventions improved knowledge [18, 19]. Another study showed that the mean of knowledge was increased from 50% to 75% following educational interventions for patients with central venous lines [20]. Educational programs were expected to improve awareness; patients with chronic diseases seek enough information about diseases and their treatments, and giving information can increase their awareness [21, 22]. The score was 1.90 on the pre-test and increased to 1.98. A score of 2 or lower is a low score and needs to improve in the patients.

The results for the perceived susceptibility showed that intervention increased it. Similarly, Nooriani et al. [23] evaluated the nutritional intervention based on HBM for hemodialysis patients and showed that educational interventions improved the perceived susceptibility. Baghiani Moghadam showed increased efficiency in designing educational messages to improve the perceived susceptibility of diabetic patients [24]. Jahanlou et al. [25] showed that educational intervention can improve perceived susceptibility. Perceived severity is a variable for the HBM construct. Perceived severity is a belief against serious threats and the attitude related to the deterioration of encountering illness effects used to evaluate the possibility of social consequences [26]. The results show that educational interventions improve the knowledge of the consequences.

The educational interventions improved the perceived severity. The results showed that the interventions improved the perceived severity after 2 months. Similarly, Shabibi et al. [27] evaluated the effects of educational interventions based on HBM for promoting self-care behaviors in patients with diabetes. They showed that educational interventions improved the perceived severity. The score was higher than 4.00, which shows that educational interventions significantly increased the perceived severity. It was at the mean of pre-intervention but increased afterward. Other studies reported similar results [14, 18]. It was reported that the perceived severity is important in preventing behaviors [22]. High perceived severity has a close relation with self-care behaviors [27]. In the current study, perceived severity increased, confirming increased self-care behaviors.

The perceived benefits increased from 3.95 in the pre-test to 4.80 in the post-test in the intervention group, which shows that educational interventions increase the perceived benefits. Similar results were reported by others [5, 27] who showed educational interventions based on HBM increased the perceived benefits. An increase in the perceived benefits increases the motivation and tendency for self-care behaviors and performing them. In sum, the educational interventions based on HBM increased motivation and tendency for self-care behaviors, and the behaviors were increased.

The score for perceived barriers was 3.12 on the pre-test (medium score) and increased to 4.09 (high score) on the post-test. The results are the same as findings reported by others [12, 17, 21], who reported that educational interventions decreased perceived barriers. Perceived barriers differ from the HBM construct and comprise physical, psychological, or financial barriers that prevent a person from conducting appropriate health behaviors [8]. An educational intervention is efficient when it can decrease barriers. The results showed that educational interventions did not decrease but increased barriers. It means that educational interventions pose physical, psychological, or financial barriers to promoting fistula care behaviors of hemodialysis patients.

The results showed that self-efficacy was 3.90 in the pre-test and increased to 4.81 in the intervention group. Other studies reported similar results [15, 20]. Self-efficacy is an important variable for the HBM construct and is a result of the educational program. It shows that educational interventions promote self-efficacy in fistula care behaviors of hemodialysis patients. The results showed that fistula care behavior increased from 1.00 in the pre-test to 1.79 in the post-test. The results were similar to those reported by previous studies [23, 26].

Conclusion

The educational intervention based on HBM improves perceived susceptibility, severity and benefits, and self-efficacy of fistula care behavior in hemodialysis patients.

Acknowledgments: The authors would like to acknowledge all the participants in hemodialytic patients of Shahid Modarres, Taliqani, and Imam Hussain Hospitals.

Ethical Permissions: It was first approved by the Ethics Committee of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences.

Conflicts of Interests: None declared by the authors.

Funding/Support: The present study was extracted from an MSc thesis in Health Education.

The kidneys regulate body fluids, electrolytes, and acid-base balance [1]. Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is increasing worldwide and is a public problem for worldwide health [2]. Kidney diseases affect over 750 million people worldwide [3].

The CKD has a 5–15% global prevalence worldwide [4]. The burden, detection, and treatment of kidney diseases vary in different countries. The magnitude and effect of kidney diseases are efficiently defined in developed and developing countries [5]. CKD is associated with raised progression to end-stage renal disease and reduced survival. Faulted renal function increases excretion products of the kidneys in the blood and leads to terminal CKD [6]. Patients with terminal CKD need replacement treatments. World Kidney Day 2019 suggests an opportunity to increase awareness of kidney diseases and suggests considering its burden and current state for prevention and management. Hemodialysis, peritoneal dialysis, and kidney transplantation are commonly used to treat CKD [6]. Hemodialysis is a replacement treatment in which a dialyzer removes blood toxins, nitrogenous wastes, and excess water from the blood and returns clear blood to the body [7]. Hemodialysis commonly lasted 4 hours and 3 times per week [8]. The patients need an arteriovenous fistula for conducting hemodialysis [6]. An arteriovenous fistula is an appropriate vascular access for the hemodialysis method because it has longer survival and low rates of complications [9]. However, arteriovenous fistula needs management and self-care before, during, and after hemodialysis [6]. It must be considered an antiseptic solution before the hemodialysis. To maintain the best conditions for hemodialysis, patients must be aware of self-care behaviors associated with arteriovenous fistula [10]. Patients must be educated about the association of arteriovenous fistula because it can help increase the number of patients who perform hemodialysis using a fistula [11, 12]. Self-care is commonly obtained in patients with enough information associated with fistula [12]. Self-care with arteriovenous fistula has a long history, and several studies have investigated it [6, 13, 14], but the health belief model (HBM) has not been investigated.

The HBM was developed to explain behaviors associated with tuberculosis screening during the 1950s. It comprises concepts that help patients prevent, screen, and control illness conditions. It includes susceptibility, severity, benefits, barriers to a behavior, cues to action, and self-efficacy [15]. Perceived susceptibility and severity are defined as a feeling of patients from threats created by their current behavioral patterns [16]. Perceived benefit is patients’ beliefs that change their behavior to have more benefits [16]. Perceived belief is defined as the tangible and psychological costs of the advised action [16]. Self-efficacy is patients’ feeling for overcoming perceived barriers [16].

Education based on HBM may help hemodialysis patients promote fistula care behaviors, but no study has investigated this. The present study investigated the effect of education based on HBM on promoting fistula care behaviors of hemodialysis patients.

Materials and Methods

Study design

The present study was an experimental and interventional study in dialysis units of different hospitals and in patients who used arteriovenous fistula for hemodialysis.

Population and sampling

This study was performed in dialysis units of hospitals affiliated with Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences. The criteria for participants to be eligible for the study were willingness to participate in the research, an arteriovenous fistula more than 6 months old on hemodialysis, performing dialysis three times a week, and having the ability to read and write. The exclusion criteria were patient mortality, unwillingness to participate, patient transfer to another section for dialysis, and having a transplant. The target population included hemodialytic patients referred to Shahid Modares, Ayatollah Taliqani, and Imam Hussain hospitals. Thirty-five patients referred to the dialysis center of Shahid Modares Hospital (n=22) and Taliqani Hospital (n=13) were selected as the intervention group, and 35 patients referred to Imam Hussain Hospital were selected as a control group.

Data collection and instrument

The data were collected from January to March 2018. The information for demographic characteristics (age, gender, education, and marital status) and clinical characteristics (dialysis period, history of hypertension, diabetes, and renal diseases) were collected by using a questionnaire designed by the authors. Information concerning awareness of self-care behaviors for hemodialysis was collected by a questionnaire designed by the authors, which included 2 questions at the 3-level and 4-level levels. A questionnaire was designed by the authors for the HBM and included variables of perceived susceptibility (2 items), perceived severity (2 items), perceived benefits (2 items), barriers (3 items), and self-efficacy (4 items). Responses were designed based on a Likert scale with five possible answers, and higher scores indicated patients’ higher frequency of variables.

Face and content validities were used to validate the questionnaires. Content validity (CVI) is a common approach for investigating content validity in instrument development. The content validity ratio (CVR) investigates the essentials of an item. To investigate the validities of CVI and CVR of the questionnaire, 10 experienced experts investigated the questionnaires and presented comments for improving the questionnaire. The comments were used, and the questionnaires were revised. To test the instrument's reliability, the questionnaire was distributed among 30 hemodialytic patients in Shohadaye Tajrish Hospital that had not been studied in the current study. Cronbach’s alpha values were 0.741, 0.760, 0.766, 0.71, 0.789, 0.776, and 0.779 for fistula care behaviors, awareness, perceived susceptibility, perceived severity, perceived benefits, perceived barriers, and self-efficacy. Values of 0.70 and higher show the reliability of the questionnaire. The questionnaires had a reliability of 0.7, and they are reliable.

Intervention

The self-made questionnaire was distributed between the control and intervention groups before interventions (pre-test) and during dialysis. Educational contents were prepared based on the pre-test. With regards to the condition and situation of patients during dialysis, the educational intervention was performed for the intervention group using personal consultation (face to face) and, in some cases, consultation sessions in pairs or triads that were followed by Q & As. All the interventions were conducted based on HBM constructs and self-care purposes. An educational session was held for 15-20 minutes, and fistula care behaviors were discussed. Instructional media, such as a guide to using fistula for hemodialytic patients, were also used. The questionnaires were collected from the same patients in Modarres and Taliqani hospitals immediately and 2 months later.

Data analysis

To analyze the effect of education on promoting hemodialytic patients’ self-care behaviors, the Chi-squared and independent-sample t-test were used by SPSS 16 software, and a repeated measure test was also used. A p<0.05 was considered as significant.

Findings

Most patients had an age mean of 55–65 years (31.4%) and 65 and 75 years (40%) in the intervention and control groups, respectively. There was no significant difference in age, gender, marital status, blood pressure, and diabetes (p>0.05). Significant differences between the groups were found for education, kidney disease history, and dialysis period (p<0.05).

The awareness score did not significantly differ between the intervention and control groups in the pre-test, post-test, and follow-up (p=0.06). The results showed significant interaction effects between time and group for the perceived susceptibility (p=0.001). The results showed decreased scores in the intervention group, but it was significantly higher in the intervention group compared to the control group (p<0.05). It can be implicated that educational interventions significantly improved the perceived susceptibility (p=0.001). The score for perceived severity was lower in the control group compared to the intervention group in the pre-test. The repeated-measure test showed that the perceived severity score of fistula care behavior was significantly higher in the intervention group compared to the control group (p<0.05), immediately and after 2 months. It means that the intervention significantly improved the perceived severity. A significant interaction between group and time was observed (p=0.001) for the perceived severity. It means that educational interventions could increase the perceived severity, which was significantly higher after 2 months. The results showed that educational intervention increased perceived benefits immediately and after 2 months (p<0.05). It means that educational intervention still improved perceived benefits after 2 months. It was observed that a significant interaction between time and group for perceived benefits (p=0.001). The intervention increased the perceived benefits. Similar to previous parts, the educational interventions perceived barriers. The results showed that the perceived barriers were significantly higher after the educational interventions (p<0.05). It means that the score for the perceived barriers was the same but increased from the pre-test to the post-test in the intervention group (p<0.05). The results showed that self-efficacy was significantly higher in the intervention group compared to the control group after educational interventions. The results showed that scores were 3.80 in all the periods, but it was significantly increased in the intervention group immediately and after 2 months (p<0.05). A significant interaction between group and time was observed for self-efficacy (p=0.001; Table 1).

Table 1. The mean of awareness, susceptibility, severity, benefits, barriers, and self-efficacy scores of hemodialytic patients concerning fistula care behavior before, immediately, and 2 months after intervention in the groups

The educational intervention improved fistula-care behavior (p<0.05). The results showed that educational interventions significantly improved fistula-care behavior scores in post-test and follow-up (p=0.001). The score was specifically higher after 2 months. A significant interaction was observed between the group and time for fistula care behavior (p=0.001). The fistula care behavior was improved during the intervention groups (Table 2).

Table 2. The mean scores of fistula-care behavior in hemodialytic patients before, immediately, and 2 months after the educational intervention in groups

Discussion

The results showed that educational intervention did not have significant effects on awareness. Daniali et al. [17] showed that educational interventions significantly improved awareness in patients with multiple sclerosis. The difference between the findings of the present study and Daniali et al. is due to disease and intervention type. Other studies also showed that educational interventions improved knowledge [18, 19]. Another study showed that the mean of knowledge was increased from 50% to 75% following educational interventions for patients with central venous lines [20]. Educational programs were expected to improve awareness; patients with chronic diseases seek enough information about diseases and their treatments, and giving information can increase their awareness [21, 22]. The score was 1.90 on the pre-test and increased to 1.98. A score of 2 or lower is a low score and needs to improve in the patients.

The results for the perceived susceptibility showed that intervention increased it. Similarly, Nooriani et al. [23] evaluated the nutritional intervention based on HBM for hemodialysis patients and showed that educational interventions improved the perceived susceptibility. Baghiani Moghadam showed increased efficiency in designing educational messages to improve the perceived susceptibility of diabetic patients [24]. Jahanlou et al. [25] showed that educational intervention can improve perceived susceptibility. Perceived severity is a variable for the HBM construct. Perceived severity is a belief against serious threats and the attitude related to the deterioration of encountering illness effects used to evaluate the possibility of social consequences [26]. The results show that educational interventions improve the knowledge of the consequences.

The educational interventions improved the perceived severity. The results showed that the interventions improved the perceived severity after 2 months. Similarly, Shabibi et al. [27] evaluated the effects of educational interventions based on HBM for promoting self-care behaviors in patients with diabetes. They showed that educational interventions improved the perceived severity. The score was higher than 4.00, which shows that educational interventions significantly increased the perceived severity. It was at the mean of pre-intervention but increased afterward. Other studies reported similar results [14, 18]. It was reported that the perceived severity is important in preventing behaviors [22]. High perceived severity has a close relation with self-care behaviors [27]. In the current study, perceived severity increased, confirming increased self-care behaviors.

The perceived benefits increased from 3.95 in the pre-test to 4.80 in the post-test in the intervention group, which shows that educational interventions increase the perceived benefits. Similar results were reported by others [5, 27] who showed educational interventions based on HBM increased the perceived benefits. An increase in the perceived benefits increases the motivation and tendency for self-care behaviors and performing them. In sum, the educational interventions based on HBM increased motivation and tendency for self-care behaviors, and the behaviors were increased.

The score for perceived barriers was 3.12 on the pre-test (medium score) and increased to 4.09 (high score) on the post-test. The results are the same as findings reported by others [12, 17, 21], who reported that educational interventions decreased perceived barriers. Perceived barriers differ from the HBM construct and comprise physical, psychological, or financial barriers that prevent a person from conducting appropriate health behaviors [8]. An educational intervention is efficient when it can decrease barriers. The results showed that educational interventions did not decrease but increased barriers. It means that educational interventions pose physical, psychological, or financial barriers to promoting fistula care behaviors of hemodialysis patients.

The results showed that self-efficacy was 3.90 in the pre-test and increased to 4.81 in the intervention group. Other studies reported similar results [15, 20]. Self-efficacy is an important variable for the HBM construct and is a result of the educational program. It shows that educational interventions promote self-efficacy in fistula care behaviors of hemodialysis patients. The results showed that fistula care behavior increased from 1.00 in the pre-test to 1.79 in the post-test. The results were similar to those reported by previous studies [23, 26].

Conclusion

The educational intervention based on HBM improves perceived susceptibility, severity and benefits, and self-efficacy of fistula care behavior in hemodialysis patients.

Acknowledgments: The authors would like to acknowledge all the participants in hemodialytic patients of Shahid Modarres, Taliqani, and Imam Hussain Hospitals.

Ethical Permissions: It was first approved by the Ethics Committee of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences.

Conflicts of Interests: None declared by the authors.

Funding/Support: The present study was extracted from an MSc thesis in Health Education.

References

1. Dhondup T, Qian Q. Electrolyte and acid-base disorders in chronic kidney disease and end-stage kidney failure. Blood Purif. 2017;43(1-3):179-88. [Link] [DOI:10.1159/000452725]

2. Pessoa NRC, Linhares FMP. Hemodialysis patients with arteriovenous fistula: Knowledge, attitude and practice. Esc Anna Nery 2015;19(1):73-9. [Link] [DOI:10.5935/1414-8145.20150010]

3. Crews DC, Bello AK, Saadi G. Burden, access, and disparities in kidney disease. Nephron. 2018;2:1-8. [Link] [DOI:10.4103/ijn.IJN_55_19]

4. De Nicola L, Zoccali C. Chronic kidney disease prevalence in the general population: Heterogeneity and concerns. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2016;31(3):331-5. [Link] [DOI:10.1093/ndt/gfv427]

5. Hill NR, Fatoba ST, Oke JL, Hirst JA, O'Callaghan CA, Lasserson DS, et al. Global prevalence of chronic kidney disease- a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2016;11(7):e0158765. [Link] [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0158765]

6. Clementino DS, de Queiroz Souza AM, Carmo da Costa Barros D, Albuquerque Carvalho DM, dos Santos CR, Nascimento Fraga S. Hemodialysis patients: The importance of self-care with the arteriovenous fistula. J Nurs UFPE online, Recife. 2018;12(7):1841-52. [Link] [DOI:10.5205/1981-8963-v12i7a234970p1841-1852-2018]

7. Fernandes EF, Soares W, Santos TC, Moriya TM, Terçariol CA, Ferreira V. Arteriovenous fistula: Self-care in patients with chronic renal disease. Medicina (Ribeirão Preto). 2013;46(4):424-8. [Link]

8. Sousa MR, Silva AE, Bezerra AL, Freitas JS, Miasso AI. Eventos adversos en hemodiálisis: Testimonios de profesionales de enfermeira. Rev Esc Enferm USP. 2013;47(1)75-82. [Link] [DOI:10.1590/S0080-62342013000100010]

9. Moreira AGM, Araújo STC, Torchi TS. Preservation of arteriovenous fistula: Conjunct actions from nursing and client. Esc Anna Nery. 2013;17(2):256-62. [Link] [DOI:10.1590/S1414-81452013000200008]

10. Sousa CN, Apostolo JL, Figueiredo MH, Dias VF, Teles P, Martins MM. Construction and validation of a scale of assessment of self-care behaviors with arteriovenous fistula in hemodialysis. Hemodial Int. 2015;19(2):306-13. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/hdi.12249]

11. Furtado AM, Lima FET. Autocuidado dos pacientes portadores de insuficiência renal crônica com a fístula artério-venosa. Rev Gaúcha Enferm. 2006;27:532-8. [Português] [Link]

12. Sousa CN, Apostolo JL, Figueiredo MH, Martins MM, Dias VF. Physical examination: How to examine the arm with arteriovenous fistula. Hemodial Int. 2013;17(2):300-6. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/j.1542-4758.2012.00714.x]

13. Tordoir J, Canaud B, Haage P, Konner K, Basci A, Fouque D, et al. EBPG on vascular access. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2007;22:ii88-ii117. [Link] [DOI:10.1093/ndt/gfm021]

14. Kukita K, Ohira S, Amano I, Naito H, Azuma N, Ikeda K, et al. 2011 update Japanese Society for dialysis therapy guidelines of vascular access construction and repair for chronic hemodialysis. Ther Apher Dial. 2015;19:1-39. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/1744-9987.12296]

15. Glanz K, Rimer BK, Viswanath K. Health behavior and health education: Theory, research, and practice. New Jersey, United States: John Wiley and Sons; 2008. [Link]

16. Bandura A. Self-efficacy: The Exercise of Control. New York: W. H. Freeman; 1997. [Link]

17. Daniali SS, Shahnazi H, Kazemi S, Marzbani E. The effect of educational intervention on knowledge and self-efficacy for pain control in patients with multiple sclerosis. Mater Sociomed. 2016;28(4):283-7. [Link] [DOI:10.5455/msm.2016.28.283-287]

18. Pereira DA, Costa NM, Sousa AL, Jardim P, Zanini CR. The effect of educational intervention on the disease knowledge of diabetes mellitus patients. Rev Lat Am Enfermagem. 2012;20(3):478-85. [Link] [DOI:10.1590/S0104-11692012000300008]

19. Yousif KI, Abu-Aisha H, Abboud OI. The effect of an educational program for vascular access care on nurses' knowledge at dialysis centers in Khartoum State, Sudan. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl. 2017;28(5):1027-33. [Arabic] [Link] [DOI:10.4103/1319-2442.215149]

20. Shrestha R. Impact of educational interventions on nurses' knowledge regarding care of patient with central venous line. J Kathmandu Med Coll. 2013;2(1):28-30. [Link] [DOI:10.3126/jkmc.v2i1.10553]

21. Solari A, Martinelli V, Trojano M, Lugaresi A, Granella F, Giordano A, et al. An information aid for newly diagnosed multiple sclerosis patients improves disease knowledge and satisfaction with care. Mult Scler. 2010;16(11):1393-405. [Link] [DOI:10.1177/1352458510380417]

22. Tariman JD, Berry D, Cochrane B, Doorenbos A, Schepp K. Preferred and actual participation roles during health care decision making in persons with cancer: A systematic review. Ann Oncol. 2010;21(6):1145-51. [Link] [DOI:10.1093/annonc/mdp534]

23. Nooriani N, Mohammadi V, Feizi A, Shahnazi H, Askari G, Ramezanzade E, et al. The effect of nutritional education based on health belief model on nutritional knowledge, health belief model constructs, and dietary intake in hemodialysis patients. Iran J Nurs Midwifery Res. 2019;24(5):372-8. [Persian] [Link] [DOI:10.4103/ijnmr.IJNMR_124_18]

24. Baghiani Moghadam MH, Taheri GH, Fallah Zadeh H, Parsa M. The effect of instructional designed SMS based on health belief model (HBM) on adoption of self-care behavior of patients with type II diabetes. Modern Care. 2014;11(1):10-8. [Persian] [Link]

25. Gahanloo SH, Ghofranipour F, Vafaei M, Kimiagar M, Heidarnia AR, Sobhani AR, et al. Assessment HBM structures along with DBA1C in diabetic patients with optimum and un favorable diabet. J Hormozgan Med School. 2008;12(1):37-42. [Persian] [Link]

26. Cismaru M. Using protection motivation theory to increase the persuasiveness of public service communications. regina: Saskatchewan institute of public policy; 2006. p. 5-27. [Link]

27. Shabibi P, Zavareh MS, Sayehmiri K, Qorbani M, Safari O, Rastegarimehr B, et al. Effect of educational intervention based on the Health Belief Model on promoting self-care behaviors of type-2 diabetes patients. Electr Phys. 2017;9(12):5960-8. [Link] [DOI:10.19082/5960]

28. Wai CT, Wong ML, Ng S, Cheok A, Tan MH, Chua W, et al. Utility of Health Belief Model in predicting compliance of screening in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;21(10):1255-62. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2036.2005.02497.x]

29. Tan MY. The relationship of health beliefs and complication prevention behaviors of Chinese individuals with Type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diab Res Clin Pract. 2004;66(1):71-7. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.diabres.2004.02.021]

30. Jadga KH, Zareban I, Alizadeh-Siuki H, Izadirad H. The impact of educational intervention based on health belief model on promoting self-care behaviors in patients with smear positive pulmonary TB. J Health Educ Health Prom Summer. 2014;2(2):143-52. [Link]

31. Karimi M, Zareban I, Montazrei A, Aminshokravi F. The impact of education based on Health Belief Model in preventive behavior of unwanted pregnancy. IJOGI. 2012;15(23):18-27. [Persian] [Link]

32. Agha Molaei T, Eftekhar H, Mohammad K. Application of health belief model to behavior change of diabetic patients. Payesh. 2005;4(4):263-9. [Persian] [Link]

33. Shamsi M, Bayati A. A survey of the prevalence of self-medication and the factors affecting it in pregnant mothers referring to health centers in Arak city. Jahrom Med J. 2010;7(3):34-42. [Persian] [Link] [DOI:10.29252/jmj.7.4.5]

34. Koch J. The role of exercise in the African- American woman with type 2 diabetes mellitus: application of the Health Belief Model. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 2002;14(3):126-9. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/j.1745-7599.2002.tb00103.x]

35. Rosenstock IM. The health belief model and preventive health behavior. Health Educ Monogr. 1974;2(4):354-86. [Link] [DOI:10.1177/109019817400200405]

36. Borhani M, Rastgarimehr B, Shafieyan Z, Mansourian M, Hoseini SM, Arzaghi SM, et al. Effects of predisposing, reinforcing and enabling factors on self-care behaviors of the patients with diabetes mellitus in the Minoodasht city, Iran. J Diabetes Metab Disord. 2015;14:14-27. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s40200-015-0139-0]

37. Olayemi SO, Oreagba IA, Akinyede A. Educational intervention and the health seeking attitude and adherence to therapy by tuberculosis patients from an urban slum in Lagos Nigeria. Niger Postgrad Med. 2009;16(4):231-5. [Link] [DOI:10.4103/1117-1936.181404]

38. Sarani M. The Study for Health Belief Model efficiency in adopting preventive behaviors in the Sistan region tuberculosis patients 2009-2010. Med Sci Health Serv Zahedan. 2011;1:152-3. [Link]

39. Atashpeikar S, JalilAzar T, HeidarZadeh M. Self care ability in hemodialysis patients. J Caring Sci. 2009;14:40-5. [Persian] [Link]

40. Abd EH, Abdel ME, Abdel FR, Ismail SS, Medhat AA. Impact of teaching guidelines on quality of life for hemodialysis patients. Nat Sci. 2011;9:214-22. [Link]