GMJ Medicine

eISSN : 2626-3041

Volume 3, Issue 2 (2024)

GMJM 2024, 3(2): 77-80 |

Back to browse issues page

Article Type:

Subject:

History

Received: 2023/11/10 | Accepted: 2024/05/2 | Published: 2024/06/8

Received: 2023/11/10 | Accepted: 2024/05/2 | Published: 2024/06/8

How to cite this article

Saboktakin L. Evaluation of Metabolic Syndrome in Children with Different Body Mass Index. GMJM 2024; 3 (2) :77-80

URL: http://gmedicine.de/article-2-227-en.html

URL: http://gmedicine.de/article-2-227-en.html

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Rights and permissions

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Authors

L. Saboktakin *

“Tuberculosis and Lung Disease Research Center” and “Department of Otorhinolaryngology”, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran

Keywords:

| Abstract (HTML) (1329 Views)

Full-Text: (742 Views)

Introduction

Metabolic syndrome is a set of disorders that, when combined, increase the risk of heart disease, stroke, and type 2 diabetes. These disorders include high blood pressure, high blood sugar, high waist fat, and abnormal levels of cholesterol or triglycerides [1]. The presence of one of these disorders does not indicate the presence of metabolic syndrome but indicates a higher risk of serious illness, and the more of these disorders a person has, the greater the risk of complications such as type 2 diabetes and heart disease [2, 3].

Metabolic syndrome is highly associated with overweight or obesity and inactivity. It is also associated with a disorder called insulin resistance. The digestive system naturally breaks down the foods we eat into sugar [4]. Insulin is a hormone made by the pancreas to help sugar enter cells and be used as fuel for cells. In patients with insulin resistance, the cells do not respond naturally to insulin, and glucose cannot enter the cells easily. As a result, even as the body makes more and more insulin and tries to lower blood sugar, blood sugar levels rise [5].

Most metabolic syndrome disorders do not have obvious signs or symptoms. One of the most visible signs is a large waist, and if your blood sugar is high, the signs and symptoms of diabetes, such as binge drinking, fatigue, and blurred vision, may show up. Chest pain or shortness of breath can cause cardiovascular complications [6]. Acanthosis Nigerians (dark spots on the skin, especially in wrinkled areas where sweating is high), excess hair growth, peripheral neuropathy (loss of sensation in the arms and legs), and retinopathy (retinal damage) in patients with insulin and high glucose resistance. Blood or type 2 diabetes is seen. Xanthoma or xanthelasma is seen in patients with severe fat disorders [7, 8].

Recent studies indicate that the prevalence of this syndrome in children has reached ten percent, and the incidence of this syndrome in children can endanger the health status of children and communities. The first goal in the treatment of pediatric metabolic syndrome is to reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes [9, 10]. The first step in successful prevention management is to determine this syndrome and its various components in different population groups, especially children. Therefore, despite the two important components of metabolic syndrome and its high in adolescents, this study aims to determine the prevalence of some components. Metabolic syndrome (abdominal obesity and hypertension) in primary school children in Tabriz was designed to have an intervention program for both children and adolescents in this study, and the first effective steps in the prevention and treatment of this. Remove the components of the metabolic syndrome.

Instrument and Methods

Study design

This prospective descriptive study was conducted in 2019 in Tabriz's health centers with the participation of 500 children under 7 years old. The sampling method was available and purposeful. Children were included in this study by observing the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Inclusion criteria included age under 7 years and parents' consent to participate in the study. Exclusion criteria included children with mental disorders, children with thyroid disorders, and children with liver problems and diseases. Also, if we noticed any abnormalities in the children during the examinations (history of rickets, history of morbid overeating, and history of overweight at birth), we excluded that child from the study process.

Procedure

An individual questionnaire (including surname, age, and gender) was completed for each child. After ten minutes of rest, children's blood pressure was measured from the right hand using an alkmercury sphygmomanometer (made in Japan). The tables presented in the fourth report on diagnosing, evaluating, and treating pediatric hypertension were used to determine hypertension. These tables show systolic and diastolic pressures by age, sex, and percentile of height. In the present study, blood pressure greater than or equal to 90 was defined as abnormal blood pressure, and blood pressure less than 90 was defined as normal blood pressure. Then, anthropometric indices were measured, including height, weight, and waist circumference. Weight measurement with Seca scales (made in Germany) with minimal clothing and without shoes with an accuracy of 100 grams. After contacting the gonia with the head, it was measured with an accuracy of half a centimeter. Waist circumference was measured while standing between the last tense and the iliac head during a normal exhalation. Then body mass index was measured using the existing formula.

Data analysis

Data were entered into SPSS 21 software, and the prevalence of obesity, central obesity, and hypertension (systolic and diastolic) was calculated using percentages and qualitative variables using a non-parametric test (chi-square). For Quantitative variables, a t-test was used.

Ethical considerations

Conscious consent was obtained from all participants' parents after explaining the research objectives and ensuring that sampling and participation in the research were free.

Findings

The mean age of patients in the non-metabolic syndrome group was 6.2±1.2 years, and the mean

age of the metabolic syndrome group 6.3±1.0 (p=0.145). The mean Body mass index of patients in the non-metabolic syndrome group was 32.8±8.7, and the mean of patients in the metabolic syndrome group was 24.2±7.0 (p=0.036).

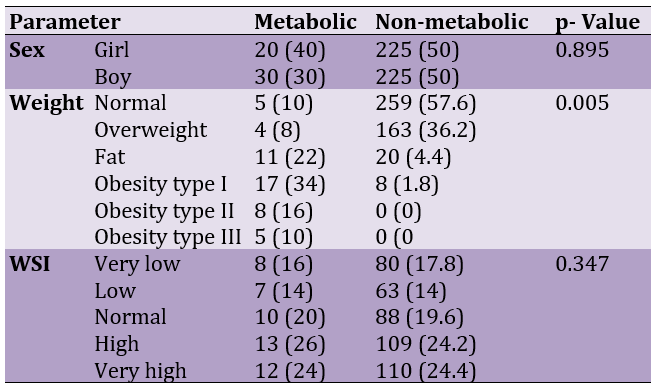

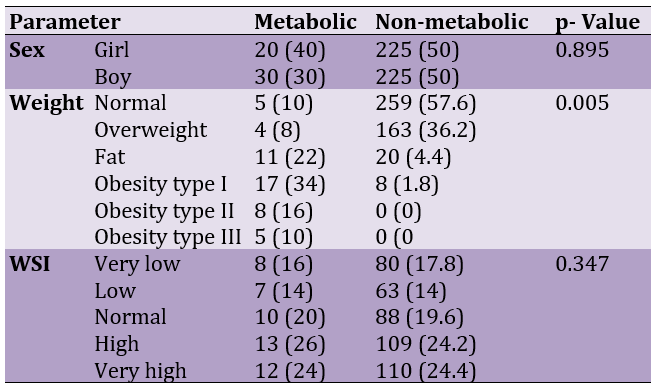

50 (10%) of the study participants had metabolic syndrome. Participants in the study were divided into two groups based on whether or not they had metabolic syndrome, and the relevant indicators were compared. Based on this classification, it was found that there are statistically significant differences between the waist ratio and metabolic syndrome as well as body mass index and metabolic syndrome between the two groups (Table 1).

The study's results showed that the body mass index of people with metabolic syndrome was significantly higher than that of people without metabolic syndrome (p=0.005).

Table 1. Comparison of the frequency of general condition of the metabolic (n=50) and non-metabolic (n=450) groups

Discussion

Experts are still unsure about the cause of metabolic syndrome. People should consider having metabolic syndrome as an alarm and prevent this serious disease in the future by making simple changes in eating and behavioral habits. Several risk factors are involved in developing this disease, some of which include the following [11, 12].

Insulin resistance: Insulin is a hormone that helps the body use glucose and convert it into energy. In insulin-resistant people, this hormone does not work properly [13]. Therefore, the body produces more insulin to fight the rise in glucose levels, which can lead to diabetes; Insulin resistance is closely related to abdominal weight gain [14].

Obesity: According to obesity experts, especially abdominal obesity increases the risk of metabolic syndrome. Having belly fat, along with fat in other parts of the body, seems to play an important role in increasing the risk of developing this syndrome. Unhealthy lifestyle: A diet high in processed foods and a lack of adequate physical activity can contribute to the disease [15, 16].

Hormonal imbalance: Hormones may play a role in the development of this syndrome; For example, polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), which affects fertility, causes hormonal imbalance and metabolic syndrome [17, 18].

The prevalence of this syndrome has increased in recent years. It is estimated that about 20 to 25 percent of adults are affected [19]. This syndrome is associated with central obesity and insulin resistance. Obesity is involved in high blood pressure, high blood LDL cholesterol (bad cholesterol), low HDL cholesterol (good cholesterol), and hyperglycemia (high blood sugar). Abdominal obesity is particularly associated with metabolic risk factors. Metabolic syndrome is a set of metabolic complications of obesity. In insulin-resistance disease, the body can not use insulin well [20]. The body needs insulin in daily life to convert sugar and starch into energy. If the body is unable to do this, diabetes or diabetes will occur. In some people, insulin resistance is inherited. Acquired factors (such as increased body fat and lack of physical activity) can cause insulin resistance and metabolic syndrome in these people. Most people with insulin resistance also have central (abdominal) obesity.

Lack of knowledge about birth weight, lack of information about the nutritional status of children, lack of information about the weight of parents and also lack of knowledge about the activity of children were some of the limitations of this study that are recommended to be addressed in future studies. Due to the high prevalence of metabolic syndrome in children under 7 years of age, it is recommended to take preventive measures for these children.

Conclusion

Two important components of metabolic syndrome (abdominal obesity and obesity) are relatively common in Tabriz children under 7 years of age. Since changes in body mass index are affected by several factors, it seems necessary to consider the underlying role of these factors in the evaluation of obese children.

Acknowledgments: None declared by the authors.

Ethical Permission: The code of ethics (IR.TBZMED.REC.1399.1037) was obtained from Tabriz University of Medical Sciences for this study.

Conflicts of Interests: None declared by the authors.

Funding/Support: Coordination with the Vice Chancellor for Health of Tabriz University of Medical Sciences for sampling in health centers in Tabriz was also done.

Metabolic syndrome is a set of disorders that, when combined, increase the risk of heart disease, stroke, and type 2 diabetes. These disorders include high blood pressure, high blood sugar, high waist fat, and abnormal levels of cholesterol or triglycerides [1]. The presence of one of these disorders does not indicate the presence of metabolic syndrome but indicates a higher risk of serious illness, and the more of these disorders a person has, the greater the risk of complications such as type 2 diabetes and heart disease [2, 3].

Metabolic syndrome is highly associated with overweight or obesity and inactivity. It is also associated with a disorder called insulin resistance. The digestive system naturally breaks down the foods we eat into sugar [4]. Insulin is a hormone made by the pancreas to help sugar enter cells and be used as fuel for cells. In patients with insulin resistance, the cells do not respond naturally to insulin, and glucose cannot enter the cells easily. As a result, even as the body makes more and more insulin and tries to lower blood sugar, blood sugar levels rise [5].

Most metabolic syndrome disorders do not have obvious signs or symptoms. One of the most visible signs is a large waist, and if your blood sugar is high, the signs and symptoms of diabetes, such as binge drinking, fatigue, and blurred vision, may show up. Chest pain or shortness of breath can cause cardiovascular complications [6]. Acanthosis Nigerians (dark spots on the skin, especially in wrinkled areas where sweating is high), excess hair growth, peripheral neuropathy (loss of sensation in the arms and legs), and retinopathy (retinal damage) in patients with insulin and high glucose resistance. Blood or type 2 diabetes is seen. Xanthoma or xanthelasma is seen in patients with severe fat disorders [7, 8].

Recent studies indicate that the prevalence of this syndrome in children has reached ten percent, and the incidence of this syndrome in children can endanger the health status of children and communities. The first goal in the treatment of pediatric metabolic syndrome is to reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes [9, 10]. The first step in successful prevention management is to determine this syndrome and its various components in different population groups, especially children. Therefore, despite the two important components of metabolic syndrome and its high in adolescents, this study aims to determine the prevalence of some components. Metabolic syndrome (abdominal obesity and hypertension) in primary school children in Tabriz was designed to have an intervention program for both children and adolescents in this study, and the first effective steps in the prevention and treatment of this. Remove the components of the metabolic syndrome.

Instrument and Methods

Study design

This prospective descriptive study was conducted in 2019 in Tabriz's health centers with the participation of 500 children under 7 years old. The sampling method was available and purposeful. Children were included in this study by observing the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Inclusion criteria included age under 7 years and parents' consent to participate in the study. Exclusion criteria included children with mental disorders, children with thyroid disorders, and children with liver problems and diseases. Also, if we noticed any abnormalities in the children during the examinations (history of rickets, history of morbid overeating, and history of overweight at birth), we excluded that child from the study process.

Procedure

An individual questionnaire (including surname, age, and gender) was completed for each child. After ten minutes of rest, children's blood pressure was measured from the right hand using an alkmercury sphygmomanometer (made in Japan). The tables presented in the fourth report on diagnosing, evaluating, and treating pediatric hypertension were used to determine hypertension. These tables show systolic and diastolic pressures by age, sex, and percentile of height. In the present study, blood pressure greater than or equal to 90 was defined as abnormal blood pressure, and blood pressure less than 90 was defined as normal blood pressure. Then, anthropometric indices were measured, including height, weight, and waist circumference. Weight measurement with Seca scales (made in Germany) with minimal clothing and without shoes with an accuracy of 100 grams. After contacting the gonia with the head, it was measured with an accuracy of half a centimeter. Waist circumference was measured while standing between the last tense and the iliac head during a normal exhalation. Then body mass index was measured using the existing formula.

Data analysis

Data were entered into SPSS 21 software, and the prevalence of obesity, central obesity, and hypertension (systolic and diastolic) was calculated using percentages and qualitative variables using a non-parametric test (chi-square). For Quantitative variables, a t-test was used.

Ethical considerations

Conscious consent was obtained from all participants' parents after explaining the research objectives and ensuring that sampling and participation in the research were free.

Findings

The mean age of patients in the non-metabolic syndrome group was 6.2±1.2 years, and the mean

age of the metabolic syndrome group 6.3±1.0 (p=0.145). The mean Body mass index of patients in the non-metabolic syndrome group was 32.8±8.7, and the mean of patients in the metabolic syndrome group was 24.2±7.0 (p=0.036).

50 (10%) of the study participants had metabolic syndrome. Participants in the study were divided into two groups based on whether or not they had metabolic syndrome, and the relevant indicators were compared. Based on this classification, it was found that there are statistically significant differences between the waist ratio and metabolic syndrome as well as body mass index and metabolic syndrome between the two groups (Table 1).

The study's results showed that the body mass index of people with metabolic syndrome was significantly higher than that of people without metabolic syndrome (p=0.005).

Table 1. Comparison of the frequency of general condition of the metabolic (n=50) and non-metabolic (n=450) groups

Discussion

Experts are still unsure about the cause of metabolic syndrome. People should consider having metabolic syndrome as an alarm and prevent this serious disease in the future by making simple changes in eating and behavioral habits. Several risk factors are involved in developing this disease, some of which include the following [11, 12].

Insulin resistance: Insulin is a hormone that helps the body use glucose and convert it into energy. In insulin-resistant people, this hormone does not work properly [13]. Therefore, the body produces more insulin to fight the rise in glucose levels, which can lead to diabetes; Insulin resistance is closely related to abdominal weight gain [14].

Obesity: According to obesity experts, especially abdominal obesity increases the risk of metabolic syndrome. Having belly fat, along with fat in other parts of the body, seems to play an important role in increasing the risk of developing this syndrome. Unhealthy lifestyle: A diet high in processed foods and a lack of adequate physical activity can contribute to the disease [15, 16].

Hormonal imbalance: Hormones may play a role in the development of this syndrome; For example, polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), which affects fertility, causes hormonal imbalance and metabolic syndrome [17, 18].

The prevalence of this syndrome has increased in recent years. It is estimated that about 20 to 25 percent of adults are affected [19]. This syndrome is associated with central obesity and insulin resistance. Obesity is involved in high blood pressure, high blood LDL cholesterol (bad cholesterol), low HDL cholesterol (good cholesterol), and hyperglycemia (high blood sugar). Abdominal obesity is particularly associated with metabolic risk factors. Metabolic syndrome is a set of metabolic complications of obesity. In insulin-resistance disease, the body can not use insulin well [20]. The body needs insulin in daily life to convert sugar and starch into energy. If the body is unable to do this, diabetes or diabetes will occur. In some people, insulin resistance is inherited. Acquired factors (such as increased body fat and lack of physical activity) can cause insulin resistance and metabolic syndrome in these people. Most people with insulin resistance also have central (abdominal) obesity.

Lack of knowledge about birth weight, lack of information about the nutritional status of children, lack of information about the weight of parents and also lack of knowledge about the activity of children were some of the limitations of this study that are recommended to be addressed in future studies. Due to the high prevalence of metabolic syndrome in children under 7 years of age, it is recommended to take preventive measures for these children.

Conclusion

Two important components of metabolic syndrome (abdominal obesity and obesity) are relatively common in Tabriz children under 7 years of age. Since changes in body mass index are affected by several factors, it seems necessary to consider the underlying role of these factors in the evaluation of obese children.

Acknowledgments: None declared by the authors.

Ethical Permission: The code of ethics (IR.TBZMED.REC.1399.1037) was obtained from Tabriz University of Medical Sciences for this study.

Conflicts of Interests: None declared by the authors.

Funding/Support: Coordination with the Vice Chancellor for Health of Tabriz University of Medical Sciences for sampling in health centers in Tabriz was also done.

References

1. DeBoer MD. Assessing and Managing the Metabolic Syndrome in Children and Adolescents. Nutrients. 2019;11(8):1788. [Link] [DOI:10.3390/nu11081788]

2. Al-Hamad D, Raman V. Metabolic syndrome in children and adolescents. Transl Pediatrics. 2017;6(4):397-407. [Link] [DOI:10.21037/tp.2017.10.02]

3. Kelishadi R, Hovsepian S, Djalalinia S, Jamshidi F, Qorbani M. A systematic review on the prevalence of metabolic syndrome in Iranian children and adolescents. J Res Med Sci. 2016;21:90. [Link] [DOI:10.4103/1735-1995.192506]

4. Wang LX, Gurka MJ, Deboer MD. Metabolic syndrome severity and lifestyle factors among adolescents. Minerva Pediatr. 2018;70(5):467-75. [Link] [DOI:10.23736/S0026-4946.18.05290-8]

5. Gepstein V, Weiss R. Obesity as the Main Risk Factor for Metabolic Syndrome in Children. Front Endocrinol. 2019;10:568. [Link] [DOI:10.3389/fendo.2019.00568]

6. Taskinen MR, Packard CJ, Borén J. Dietary Fructose and the metabolic syndrome. Nutrients. 2019;11(9):1987. [Link] [DOI:10.3390/nu11091987]

7. Mortera RR, Bains Y, Gugliucci A. Fructose at the crossroads of the metabolic syndrome and obesity epidemics. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed). 2019;24(2):186-211. [Link] [DOI:10.2741/4713]

8. Weihe P, Weihrauch-Blüher S. Metabolic syndrome in children and adolescents: diagnostic criteria, therapeutic options and perspectives. Curr Obes Rep. 2019;8(4):472-9. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/s13679-019-00357-x]

9. Swinburn BA, Kraak VI, Allender S, Atkins VJ, Baker PI, Bogard JR, et al. The global syndemic of obesity, undernutrition, and climate change: the Lancet Commission report. Lancet (London, England). 2019;393(18):791-846. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32822-8]

10. Choukem SP, Tochie JN, Sibetcheu AT, Nansseu JR, Hamilton-Shield JP. Overweight/obesity and associated cardiovascular risk factors in sub-Saharan African children and adolescents: a scoping review. Int J Pediatric Endocrinol. 2020;2020:1-3. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s13633-020-0076-7]

11. Zhu Y, Zheng H, Zou Z, Jing J, Ma Y, Wang H, et al. Metabolic syndrome and related factors in Chinese children and adolescents: analysis from a Chinese national study. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2020;27(6):534-44. [Link] [DOI:10.5551/jat.50591]

12. Mahajan N, Kshatriya GH. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome and associated risk factors among tribal adolescents of Gujarat. Diabetes Metab Syndr Clin Res Rev. 2020;14(5):995-9. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.dsx.2020.06.040]

13. Dejavitte RA, Enes CC, Nucci LB. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome and its associated factors in overweight and obese adolescents. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2020;33(2):233-9. [Link] [DOI:10.1515/jpem-2019-0369]

14. Bekel GE, Thupayagale-Tshweneagae G. Prevalence and associated factors of metabolic syndrome and its individual components among adolescents. Int J Public Health Sci. 2020;9(1):46-56. [Link] [DOI:10.11591/ijphs.v9i1.20383]

15. Ahmadi N, Seyed Mahmood SA, Mohammadi MR, Mirzaei M, Mehrparvar AH, Ardekani SM, et al. Prevalence of abdominal obesity and metabolic syndrome in children and adolescents: A community based cross-sectional study. Iranian J Public Health. 2020;49(2):360. [Link] [DOI:10.18502/ijph.v49i2.3106]

16. Zhao Y, Yu Y, Li H, Li M, Zhang D, Guo D, et al. The association between metabolic syndrome and biochemical markers in beijing adolescents. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(22):4557. [Link] [DOI:10.3390/ijerph16224557]

17. Zhang Y, Hu J, Li Z, Li T, Chen M, Wu L, et al. A novel indicator of lipid accumulation product associated with metabolic syndrome in Chinese children and adolescents. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes Targets Therapy. 2019;12:2075. [Link] [DOI:10.2147/DMSO.S221786]

18. Wang J, Perona JS, Schmidt-RioValle J, Chen Y, Jing J, González-Jiménez E. metabolic syndrome and its associated early-life factors among Chinese and spanish adolescents: a pilot study. Nutrients. 2019;11(7):1568. [Link] [DOI:10.3390/nu11071568]

19. de Oliveira RG, Guedes, Nutr DP. Determinants of lifestyle associated with metabolic syndrome in Brazilian adolescents. Hosp. 2019;36(4):826-33. [Link] [DOI:10.20960/nh.02459]

20. Suebsamran P, Pimpak T, Thani P, Chamnan P. The metabolic syndrome and health behaviors in school children aged 13-16 years in ubon ratchathani: UMeSIA project. Metab Syndr Related Disord. 2018;16(8):425-32. [Link] [DOI:10.1089/met.2017.0150]