GMJ Medicine

eISSN : 2626-3041

Volume 4, Issue 2 (2025)

GMJM 2025, 4(2): 43-46 |

Back to browse issues page

Article Type:

Subject:

History

Received: 2024/09/19 | Accepted: 2025/03/25 | Published: 2025/05/5

Received: 2024/09/19 | Accepted: 2025/03/25 | Published: 2025/05/5

How to cite this article

Hammoudi D, Sanyaolu A, Adofo D, Antoine I. Effect of Cigarette Smoking on Lung Capacity of Active-, Previous-, and Non-Smoker Students. GMJM 2025; 4 (2) :43-46

URL: http://gmedicine.de/article-2-249-en.html

URL: http://gmedicine.de/article-2-249-en.html

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Rights and permissions

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

1- Saint James School of Medicine, Anguilla, BWI

Keywords:

| Abstract (HTML) (3487 Views)

Full-Text: (816 Views)

Introduction

The continuous exposure of tissues of the respiratory tract to abundant concentrations of radicals, reactive oxygen and nitrogen species trigger a pleiotropic adaptive response aimed at restoring tissues homeostasis [1]. Transcription factor NF-E2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) have been identified as a regulator of cellular antioxidant response in defending tissues against the damaging components present in cigarette smoke [1].

Chronic exposure of tissues of the lungs to cigarette smoke leads to respiratory diseases such as Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD), emphysema, chronic bronchitis and lung cancer [2]. Epidemiologic studies show smoking causes about 90% of all lung cancer deaths in men and women and more women die from lung cancer each year than from breast cancer where as 80% of all deaths from chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) are caused by smoking [3]. Second hand smoke also contains toxic chemicals that can cause severe asthma and respiratory infections in adults and children alike [4].

Cigarette smoke predisposes a person to a lot of preventable diseases. We aimed at evaluating the possible effect of cigarette smoking on total lung capacity of active-, previous and non-smokers.

Materials and Methods

Study design, setting and participants

A cross-sectional of 77 students from the St. James School of Medicine, Anguilla campus in the Caribbean who are active smokers, previous smokers or non-smokers were randomly sampled with consent using questionnaire based study and measurement of FEV/FVC ratio was done. The study protocol was approved by the Research in Health and Medicine committee of the St. James School of Medicine, Anguilla, campus. Participants in the study were recruited from the Doctor of Medicine (MD) 2 and (MD) 3 class of summer 2014 and eligibility included students who are active, previous and non-smokers. Among the 77 participants, 34 were males and 43 were females aged between 20 and 49 years. Questionnaires that inquired about their demographics, smoking habits, respiratory symptoms, history of respiratory diseases, surgeries, and other respiratory medications was administered to each selected student.

Measurements

Each subject was self-classified as a non-smoker, ex-smoker or current smoker. Vital statistic such as gender, height, age, race, weight and length of exposure to cigarette smoke were vital input that determined their respiratory requirements. A minimum of three acceptable expiratory maneuvers was obtained [5]. During each test, three FEV-FVC measurements were recorded and the one corresponding to maximum FEV was selected [6]. The measurements were repeated approximately one month apart using the Winspiro PRO 5.2 Spirometer. The Spirometer test was repeated approximately one month apart to verify if there was any significant change in the FVC, FEV and hence the FEV/FVC ratio.

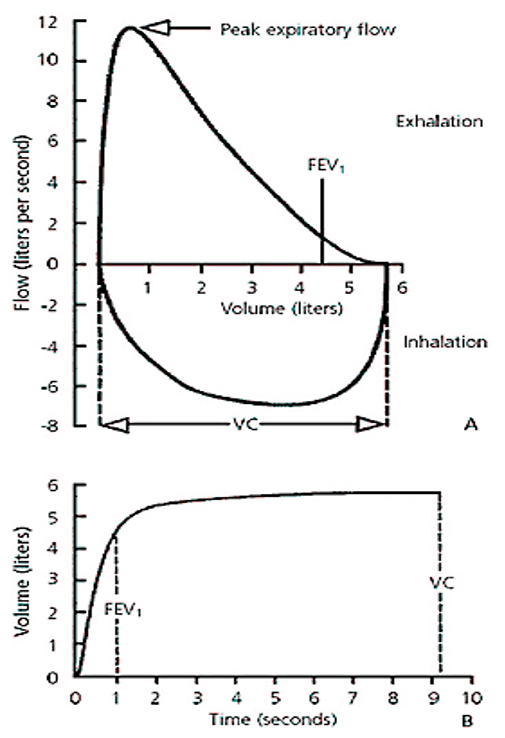

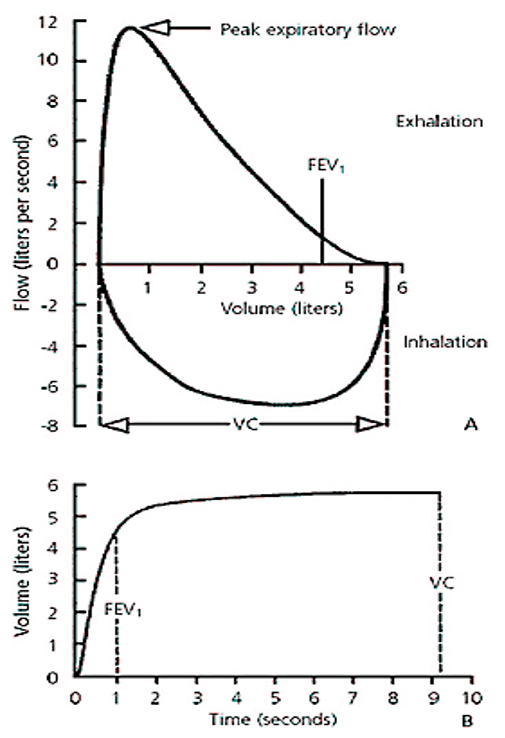

The Spirometer measures the rate at which the lung changes volume during forced breathing maneuvers. Participants started with full inhalation, followed by a forced expiration that rapidly emptied the lungs until a plateau in exhaled volume was reached. These efforts were recorded and graphed from which the FVC, FEV, FEV/FVC ratio and TLC were obtained as exemplified in Figure 1 [6].

Figure 1. Normal spirometric flow diagram. (A) Flow-volume curve. (B) Volume-time curve (FEV1: Forced Expiratory Volume in one second; FVC/VC: Forced Vital Capacity; TLC: Total Lung Capacity)

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using Epi-info 7. Frequency distribution for the variables was estimated and linear regression analysis was used to analyze the independent and dependent variables; Fisher’s test (F-test) was used to test the statistical significance. Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) was used to test means of variables in multivariate analysis.

Findings

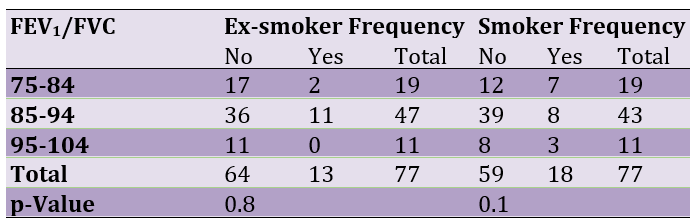

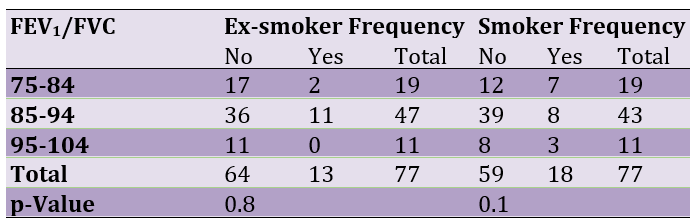

The FEV/FVC ratio was group into ranges to make the data manageable. The frequency shows the number of people that corresponded to the given ranges. The ex-smoker ‘NO’ frequency corresponds to active smokers and non-smokers whereas the ex-smoker ‘YES’ frequency corresponds to participants that have actually stopped smoking.

Table 1 shows the frequency distribution of ex-smokers and smokers with respect to their FEV/FVC ratio in the first experiment (Test 1).

Table 1. Frequency of ex-smoker and smoker status for FEV1/FVC ratio in Test 1

Table 2 shows the frequency distribution of ex-smokers and smokers with respect to their FEV/FVC ratio in the second experiment (Test 2).

Table 2. Frequency of ex-smoker and smoker status for FEV1/FVC ratio in Test 2

Table 3 shows the comparative frequency distribution of females and males with respect to their FEV/FVC ratio for the first and second experiment (Tests 1 & 2).

Table 3. Frequency of Females & Males for FEV/FVC ratio in Tests 1 & 2

Tables 4 shows the comparative frequency distribution of smokers, ex-smokers and non-smokers with respect to their FEV/FVC ratio and races (Tests 1 & 2).

Table 4. Means of FEV/FVC ratio vs. race in Tests 1 & 2

Table 5 shows the comparative frequency distribution of smokers, ex-smokers and non-smokers with respect to their FEV/FVC ratio for the first and second experiment (Tests 1 & 2).

Table 5. Frequency of smokers, ex-smokers and nonsmokers vs. FEV1/FVC ratio

Discussion

Our analysis revealed that FEV/FVC ratio had a mean of 86.6 for smokers, 89.1 for non-smokers and 88.9 for ex-smokers for Test 1 and 85.9 for smokers, 88.5 for non-smokers and 89.8 for ex-smokers for Test 2. The mean FEV/FVC ratio for ex-smokers was slightly lower than that for non-smokers in Test 1 with no significant difference but higher than both smokers and non-smokers in Test 2. Thus ex-smokers in Test 2 had a better recovery of lung function than non-smokers after stopping smoking. Chiappa et al. reported that co-effect of smoking with asthma or COPD or combined asthma and COPD has more severe impact on ageing than smoking, asthma, COPD or combined asthma and COPD alone; furthermore, it reported that the rate of decline of lung function is faster in smokers with emphysema than in ex-smokers with emphysema [7]. The p-values of 0.8 for ex-smokers ‘No’ and ex-smoker ‘Yes’ for Test 1 and p-value of 0.1 for smoker ‘No’ and smoker ‘Yes’ was not statistically significant in our study (p>0.05 at 95% confidence interval for all our results). The same trend was observed for Test 2 with ex-smokers ‘No’ and ex-smoker ‘Yes’ having a p-value of 0.35 and p-value of 0.16 for smoker ‘No’ and smoker ‘Yes’, respectively. The p-value was also statistically not significant. The FEV/FVC ratio by sex was higher in females for both Tests 1 and 2. Our results were consistent with that by Stanjevic et al. [8], who found sex differences are apparent, with females having greater predicted values of FEV/FVC than males at all ages and most marked in late puberty.

There were significant differences among the races with Caucasians having the lowest mean value of 86.04 and 85.88 for Tests 1 and 2, respectively and participants of African descent came next with a mean of 89.5 and 88.2 for Tests 1 and 2, respectively. Asians scored the highest among the races with a mean reading of 89.9 and 89.41 for Tests 1 and 2, respectively. This finding is contrary to that found by Barreiro et al. [6] with Caucasians having a greater FEV and FVC than blacks and Asians but our results is consistent with Agaku et al. [9], which showed that Asians smoked less compared with Blacks and Whites.

The mean FEV1/FVC ratio was higher with more than 0.7 for smokers, ex-smokers and non-smokers. In restrictive diseases, the absolute FEV/FVC ratio may be normal or increased whiles the FEV and FVC are decreased in obstructive diseases. The ratio varies based on age, sex, height and weight [7]. In our study the mean ratios for FEV/FVC were higher than 0.7 for all smoking habits investigated. Other studies show that the FEV/FVC of 0.7 is not attained until around 50 years of age in males and considerably later in females, but is considerably higher during childhood and lower in the elderly [6].

The p-values for the smoke status showed no statistically significant differences among the smoke status at a 95% confidence interval; therefore, our hypothesis was rejected and we are unable to accept the alternative because of insufficient data, time and other confounding factors that may be present in the research. Particulate matter in cigarette with numerous chemicals like reactive oxygen and nitrogen species, promote cellular apoptosis, increase inflammation and necrosis, which might leads to respiratory diseases like COPD, emphysema and asthma [10].

Conclusion

The FEV/FVC ratio is lower in smokers compared to non-smokers and ex-smokers though not statistically significant. There is a higher ratio for females than males and Asians FEV/FVC ratio scores are the highest among the races.

Acknowledgements: None declared by the authors.

Ethical Permissions: Approval for the study was obtained from the Saint James School of Medicine Research Committee.

Conflicts of Interests: None declared by the authors.

Authors’ Contribution: This work was carried out in collaboration between all authors. Author DH designed the study and made professional content to the manuscript, authors DA and IA wrote the first draft of the manuscript and managed the literature searches, Author AS did the analyses of the study, and finally, authors AS and DH made corrections to manuscript and prepared final draft for submission. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding/Support: Provided by the Saint James School of Medicine Research Committee.

The continuous exposure of tissues of the respiratory tract to abundant concentrations of radicals, reactive oxygen and nitrogen species trigger a pleiotropic adaptive response aimed at restoring tissues homeostasis [1]. Transcription factor NF-E2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) have been identified as a regulator of cellular antioxidant response in defending tissues against the damaging components present in cigarette smoke [1].

Chronic exposure of tissues of the lungs to cigarette smoke leads to respiratory diseases such as Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD), emphysema, chronic bronchitis and lung cancer [2]. Epidemiologic studies show smoking causes about 90% of all lung cancer deaths in men and women and more women die from lung cancer each year than from breast cancer where as 80% of all deaths from chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) are caused by smoking [3]. Second hand smoke also contains toxic chemicals that can cause severe asthma and respiratory infections in adults and children alike [4].

Cigarette smoke predisposes a person to a lot of preventable diseases. We aimed at evaluating the possible effect of cigarette smoking on total lung capacity of active-, previous and non-smokers.

Materials and Methods

Study design, setting and participants

A cross-sectional of 77 students from the St. James School of Medicine, Anguilla campus in the Caribbean who are active smokers, previous smokers or non-smokers were randomly sampled with consent using questionnaire based study and measurement of FEV/FVC ratio was done. The study protocol was approved by the Research in Health and Medicine committee of the St. James School of Medicine, Anguilla, campus. Participants in the study were recruited from the Doctor of Medicine (MD) 2 and (MD) 3 class of summer 2014 and eligibility included students who are active, previous and non-smokers. Among the 77 participants, 34 were males and 43 were females aged between 20 and 49 years. Questionnaires that inquired about their demographics, smoking habits, respiratory symptoms, history of respiratory diseases, surgeries, and other respiratory medications was administered to each selected student.

Measurements

Each subject was self-classified as a non-smoker, ex-smoker or current smoker. Vital statistic such as gender, height, age, race, weight and length of exposure to cigarette smoke were vital input that determined their respiratory requirements. A minimum of three acceptable expiratory maneuvers was obtained [5]. During each test, three FEV-FVC measurements were recorded and the one corresponding to maximum FEV was selected [6]. The measurements were repeated approximately one month apart using the Winspiro PRO 5.2 Spirometer. The Spirometer test was repeated approximately one month apart to verify if there was any significant change in the FVC, FEV and hence the FEV/FVC ratio.

The Spirometer measures the rate at which the lung changes volume during forced breathing maneuvers. Participants started with full inhalation, followed by a forced expiration that rapidly emptied the lungs until a plateau in exhaled volume was reached. These efforts were recorded and graphed from which the FVC, FEV, FEV/FVC ratio and TLC were obtained as exemplified in Figure 1 [6].

Figure 1. Normal spirometric flow diagram. (A) Flow-volume curve. (B) Volume-time curve (FEV1: Forced Expiratory Volume in one second; FVC/VC: Forced Vital Capacity; TLC: Total Lung Capacity)

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using Epi-info 7. Frequency distribution for the variables was estimated and linear regression analysis was used to analyze the independent and dependent variables; Fisher’s test (F-test) was used to test the statistical significance. Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) was used to test means of variables in multivariate analysis.

Findings

The FEV/FVC ratio was group into ranges to make the data manageable. The frequency shows the number of people that corresponded to the given ranges. The ex-smoker ‘NO’ frequency corresponds to active smokers and non-smokers whereas the ex-smoker ‘YES’ frequency corresponds to participants that have actually stopped smoking.

Table 1 shows the frequency distribution of ex-smokers and smokers with respect to their FEV/FVC ratio in the first experiment (Test 1).

Table 1. Frequency of ex-smoker and smoker status for FEV1/FVC ratio in Test 1

Table 2 shows the frequency distribution of ex-smokers and smokers with respect to their FEV/FVC ratio in the second experiment (Test 2).

Table 2. Frequency of ex-smoker and smoker status for FEV1/FVC ratio in Test 2

Table 3 shows the comparative frequency distribution of females and males with respect to their FEV/FVC ratio for the first and second experiment (Tests 1 & 2).

Table 3. Frequency of Females & Males for FEV/FVC ratio in Tests 1 & 2

Tables 4 shows the comparative frequency distribution of smokers, ex-smokers and non-smokers with respect to their FEV/FVC ratio and races (Tests 1 & 2).

Table 4. Means of FEV/FVC ratio vs. race in Tests 1 & 2

Table 5 shows the comparative frequency distribution of smokers, ex-smokers and non-smokers with respect to their FEV/FVC ratio for the first and second experiment (Tests 1 & 2).

Table 5. Frequency of smokers, ex-smokers and nonsmokers vs. FEV1/FVC ratio

Discussion

Our analysis revealed that FEV/FVC ratio had a mean of 86.6 for smokers, 89.1 for non-smokers and 88.9 for ex-smokers for Test 1 and 85.9 for smokers, 88.5 for non-smokers and 89.8 for ex-smokers for Test 2. The mean FEV/FVC ratio for ex-smokers was slightly lower than that for non-smokers in Test 1 with no significant difference but higher than both smokers and non-smokers in Test 2. Thus ex-smokers in Test 2 had a better recovery of lung function than non-smokers after stopping smoking. Chiappa et al. reported that co-effect of smoking with asthma or COPD or combined asthma and COPD has more severe impact on ageing than smoking, asthma, COPD or combined asthma and COPD alone; furthermore, it reported that the rate of decline of lung function is faster in smokers with emphysema than in ex-smokers with emphysema [7]. The p-values of 0.8 for ex-smokers ‘No’ and ex-smoker ‘Yes’ for Test 1 and p-value of 0.1 for smoker ‘No’ and smoker ‘Yes’ was not statistically significant in our study (p>0.05 at 95% confidence interval for all our results). The same trend was observed for Test 2 with ex-smokers ‘No’ and ex-smoker ‘Yes’ having a p-value of 0.35 and p-value of 0.16 for smoker ‘No’ and smoker ‘Yes’, respectively. The p-value was also statistically not significant. The FEV/FVC ratio by sex was higher in females for both Tests 1 and 2. Our results were consistent with that by Stanjevic et al. [8], who found sex differences are apparent, with females having greater predicted values of FEV/FVC than males at all ages and most marked in late puberty.

There were significant differences among the races with Caucasians having the lowest mean value of 86.04 and 85.88 for Tests 1 and 2, respectively and participants of African descent came next with a mean of 89.5 and 88.2 for Tests 1 and 2, respectively. Asians scored the highest among the races with a mean reading of 89.9 and 89.41 for Tests 1 and 2, respectively. This finding is contrary to that found by Barreiro et al. [6] with Caucasians having a greater FEV and FVC than blacks and Asians but our results is consistent with Agaku et al. [9], which showed that Asians smoked less compared with Blacks and Whites.

The mean FEV1/FVC ratio was higher with more than 0.7 for smokers, ex-smokers and non-smokers. In restrictive diseases, the absolute FEV/FVC ratio may be normal or increased whiles the FEV and FVC are decreased in obstructive diseases. The ratio varies based on age, sex, height and weight [7]. In our study the mean ratios for FEV/FVC were higher than 0.7 for all smoking habits investigated. Other studies show that the FEV/FVC of 0.7 is not attained until around 50 years of age in males and considerably later in females, but is considerably higher during childhood and lower in the elderly [6].

The p-values for the smoke status showed no statistically significant differences among the smoke status at a 95% confidence interval; therefore, our hypothesis was rejected and we are unable to accept the alternative because of insufficient data, time and other confounding factors that may be present in the research. Particulate matter in cigarette with numerous chemicals like reactive oxygen and nitrogen species, promote cellular apoptosis, increase inflammation and necrosis, which might leads to respiratory diseases like COPD, emphysema and asthma [10].

Conclusion

The FEV/FVC ratio is lower in smokers compared to non-smokers and ex-smokers though not statistically significant. There is a higher ratio for females than males and Asians FEV/FVC ratio scores are the highest among the races.

Acknowledgements: None declared by the authors.

Ethical Permissions: Approval for the study was obtained from the Saint James School of Medicine Research Committee.

Conflicts of Interests: None declared by the authors.

Authors’ Contribution: This work was carried out in collaboration between all authors. Author DH designed the study and made professional content to the manuscript, authors DA and IA wrote the first draft of the manuscript and managed the literature searches, Author AS did the analyses of the study, and finally, authors AS and DH made corrections to manuscript and prepared final draft for submission. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding/Support: Provided by the Saint James School of Medicine Research Committee.

References

1. Müller T, Hengstermann A. Nrf2: Friend and foe in preventing cigarette smoking-dependent lung disease. Chem Res Toxicol. 2012;25(9):1805-24. [Link] [DOI:10.1021/tx300145n]

2. National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (US) Office on Smoking and Health. The health consequences of smoking- 50 years of progress: A report of the surgeon general. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US). 2014;27. [Link]

3. Satcher D, Thompson TG, Koplan JP. Women and smoking: A report of the Surgeon General. Nicotine Tob Res. 2002;4(1):7-20. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/14622200210135650]

4. Stevenson CS, Belvisi MG. Preclinical animal models of asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Expert Rev Respir Med. 2008;2(5):631-43. [Link] [DOI:10.1586/17476348.2.5.631]

5. Standardization of Spirometry, 1994 Update. American Thoracic Society. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995;152(3):1107-36. [Link] [DOI:10.1164/ajrccm.152.3.7663792]

6. Barreiro TJ, Perillo I. An approach to interpreting spirometry. Am Fam physician. 2004;69(5):1107-16. [Link]

7. Chiappa S, Winn J, Viñuela A, Tipney H, Spector TD. A probabilistic model of biological ageing of the lungs for analysing the effects of smoking, asthma and COPD. Respir Rres. 2013;14(1):60. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/1465-9921-14-60]

8. Stanojevic S, Wade A, Stocks J, Hankinson J, Coates AL, Pan H, et al. Reference ranges for spirometry across all ages: A new approach. Am J Resp Crit Care Med. 2008;177(3):253-60. [Link] [DOI:10.1164/rccm.200708-1248OC]

9. Agaku IT, King BA, Dube SR. Current cigarette smoking among adults-United States, 2005-2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63(2):29-34. [Link]

10. Valavanidis A, Vlachogianni T, Fiotakis K. Tobacco smoke: Involvement of reactive oxygen species and stable free radicals in mechanisms of oxidative damage, carcinogenesis and synergistic effects with other respirable particles. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2009;6(2):445-62. [Link] [DOI:10.3390/ijerph6020445]