GMJ Medicine

eISSN : 2626-3041

Volume 4, Issue 2 (2025)

GMJM 2025, 4(2): 59-63 |

Back to browse issues page

Article Type:

Subject:

History

Received: 2024/11/28 | Accepted: 2025/03/15 | Published: 2025/05/3

Received: 2024/11/28 | Accepted: 2025/03/15 | Published: 2025/05/3

How to cite this article

Sedighi S, Nasiri B, Alipoor R, MoradiKor N. Modulation of 6-Gingerolin Antidepressant-like Effects in Mice Model. GMJM 2025; 4 (2) :59-63

URL: http://gmedicine.de/article-2-253-en.html

URL: http://gmedicine.de/article-2-253-en.html

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Rights and permissions

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

1- Tehran Medical Branch, Islamic Azad University, Tehran, Iran

2- Lorestan University of Medical Sciences, Khorramabad, Iran

3- Hormozgan University of Medical Sciences, Bandar Abbas, Iran

4- International Center for Neuroscience Research, Institute for Intelligent Research, Tbilisi, Georgia

2- Lorestan University of Medical Sciences, Khorramabad, Iran

3- Hormozgan University of Medical Sciences, Bandar Abbas, Iran

4- International Center for Neuroscience Research, Institute for Intelligent Research, Tbilisi, Georgia

Keywords:

| Abstract (HTML) (3002 Views)

Full-Text: (755 Views)

Introduction

Major depressive disorder has been known a complex psychiatric disorder with unknown cause which will involve up to 20% of the individuals during their lifetime [1] and it causes disability in people [2]. It has been known to have some symptoms including adverse effects on mood, interest, feeling, hope, appetite, sleep, performance and social relationships [3].

Oxidative stress is result of excessive formation offree radicals and it is also attributed to antioxidant defense mechanism which maintains the cells removing free radicals [4]. Oxidative stress is involved in some psychiatric disorders [5, 6] which could be attributed to excessive oxygen consumption and lipid-rich compounds of the brain [7, 8]. Studies have related depression with faulted antioxidative enzyme activities [9-11].

The faulted antioxidant system could reduce the protection against reactive oxygen species (ROS) [9]. Elevated ROS in depression has been related with increased levels of malondialdehyde and arachidonic acid [9]. It has been reported increased oxidative stress in the rats exposed to stress [12]. These evidences suggest therapeutic activity of antioxidant compounds for treatment of depression [10]. 6-Gingerol is known as one phenolic compound which is found in some plants in Zingiberaceae family including ginger, cardamom and grain of paradise. It has been known to have some properties such as cognitive enhancer [13], anti-apoptotic [14], antioxidant and anti-inflammatory [15]. It has been reported effect of ginger on gastric similar to metoclopramide, a 5-HT4 receptor agonist with antagonist properties at 5-HT3 receptors through a selective 5-HT3 receptor antagonist [16, 17].

This study was thus conducted to evaluate the antidepressant-like activity of gingerol in mice model.

Materials and Methods

Materials

Gingerol powder and DMSO (Dimethyl sulphoxide) were purchased from Chromadex (Santa Ana, CA, USA) and Scharlo (Spain), respectively.

Animals

A number of 24 male NMRI mice, 4wk of age with 28±2g weight, were purchased from Pasteur Institute (Tehran, Iran). Those were maintained under lighting/darking program (12h:12h). Animals had free access to water and feed. Commercial feed was purchased from Razi Vaccine and Serum Research Institute (Karaj-Iran). All the used procedures were approved by National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (NIH Publications No. 8023, revised 1978).

Acute toxicity test

Previous procedures [18] were used to evaluate the acute toxicity test. Following 24 h food restriction,

24 mice were divided into 4 groups and intrapritoeanally received 200, 400, 800 and 1200mg/kg gingerol dissolved in DMSO. Following treatment, animals were considered for some toxicity signs and behavioral symptoms including locomotor activity, changes in physical appearancerespiratory distress, coma, and mortality for 72h. This action was conducted for 10 days and to be healthiness and mortality were recorded [19]. We did not observe any mortality and only dizziness was observed in levels of 800-1200mg/kg. Thus, we selected levels of 100 and 300mg/kg for future studies.

Tail suspension test

Tail suspension test was conducted as reported by previous studies and total period of immobility was considered as reported by previous studies [20]. Animals were divided into 4 groups with 6 mice and treated by follow protocol:

1) Vehicle group: mice intra pritoeanally received normal saline (10ml/kg);

2) G-100 mice intrapritoeanally received 100mg/kg gingerol;

3) G-200 mice intrapritoeanally received 200mg/kg gingerol; and

4) Fluoxetine: mice intra pritoeanally received 20 mg/kgfluoxetine.

To evaluate the tail suspension test, total period of immobility time was registered by using a chronometer. Decreased immobility time was considered as a criteria for antidepressant activity [21, 22].

Serotonergic system in the antidepressant-like effect of gingerol

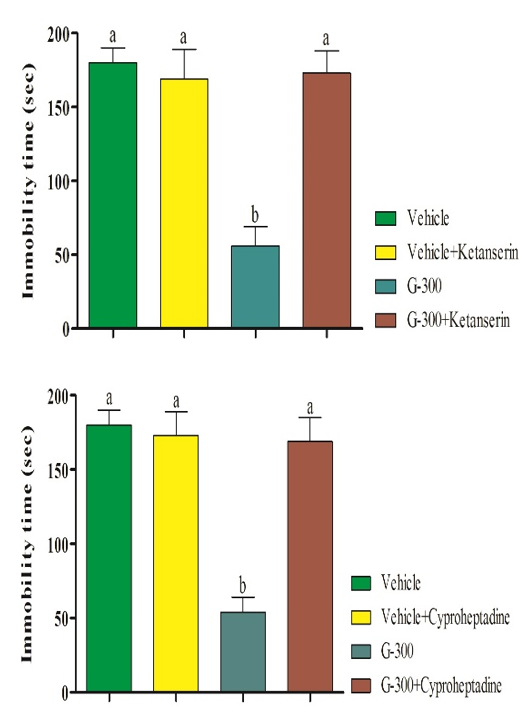

To investigate the serotonergic system, pre-treatment with PCPA, blocker of 5HT synthesis, was conducted (once/d for 3consecutive days). Since the best responses were observed in 300mg/kg gingerol, same dose was used in future trials. Following pre-treatment with PCPA, animals were treated with 300mg/kg gingerol, 15min after last administration of PCPA. Animals were submitted to tail suspension test after administration of gingerol [23]. To evaluate the involvement of 5HT1 receptor, mice were pre-treated withWAY100135 (10mg/kg), treated with 300mg/kg gingerol60 min after pre-treatment and exposed to tail suspension test after administration of gingerol [24]. To assess the involvement the 5HT2 receptor, animals were pre-treated with ketanserin and cyproheptadine, treated with 300mg/kg gingerol 60 min after pre-treatment and finally submitted to ail suspension test [25, 26].

Open field test

To evaluate the psychomotor stimulant activity, OFT was conducted as reported by others [28]. Each mouse was grouped in Plexiglas boxes (40×60×50cm). All the crossings and rearing were registered. We considered crossing as locomotors activity and rearing as exploratory behavior.

Statistical analysis

The data were reported as mean± standard deviation (Mean±SD) and analyzed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Tukey post-hoc test was used to comparethe groups. A level of p<0.05 was considered assignificant. The figures were illustrated by Prism 7 (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA).

Findings

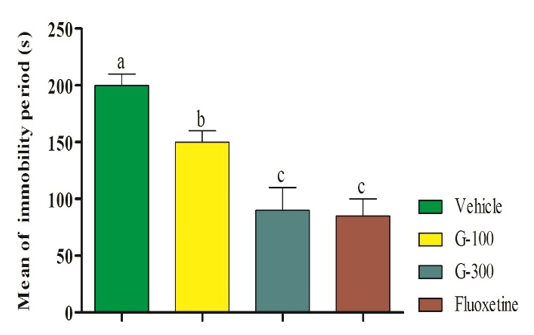

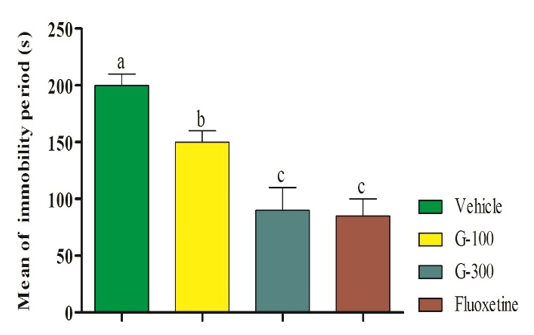

Administration of gingerol could significantly decrease immobility time (p<0.05). Immobility was decreased with increasing dose, so that lowest immobility time was observed in mice administrated with 300mg gingerol. There was no significant difference between fluoextine with 300mg gingerol (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Effect of intra-pritoeanal administration of 6-gingerol in tail suspension test. The data are shown in mean±SD. Superscripts (a-c) show significant difference among groups. The data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA

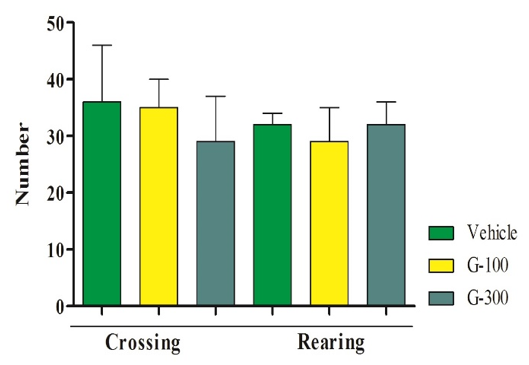

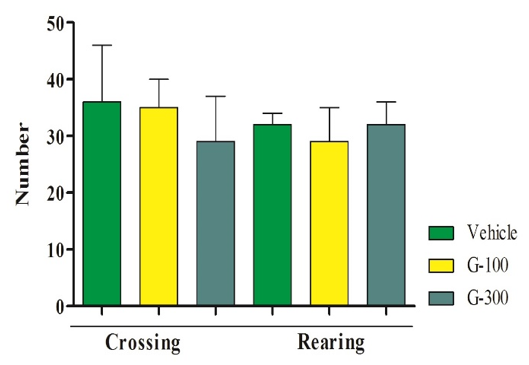

Number of OFT was not different among different groups (p>0.05; Figure 2).

Figure 2. Effect of gingerol in OFT in mice.The data are shown in mean±SD. Superscripts (a-c) show significant difference among groups. The data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA

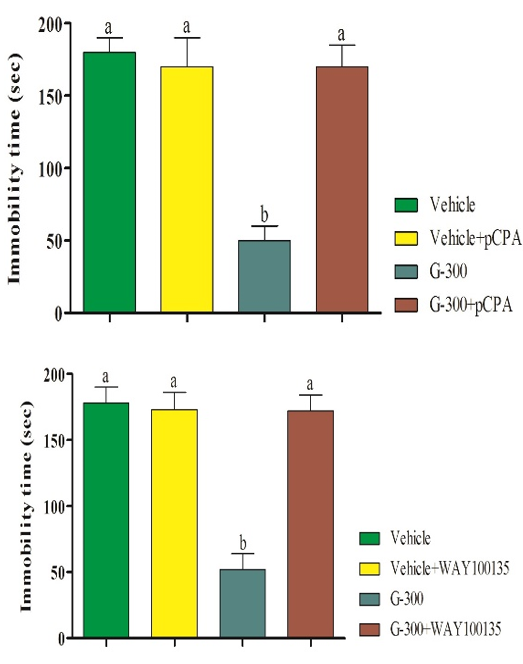

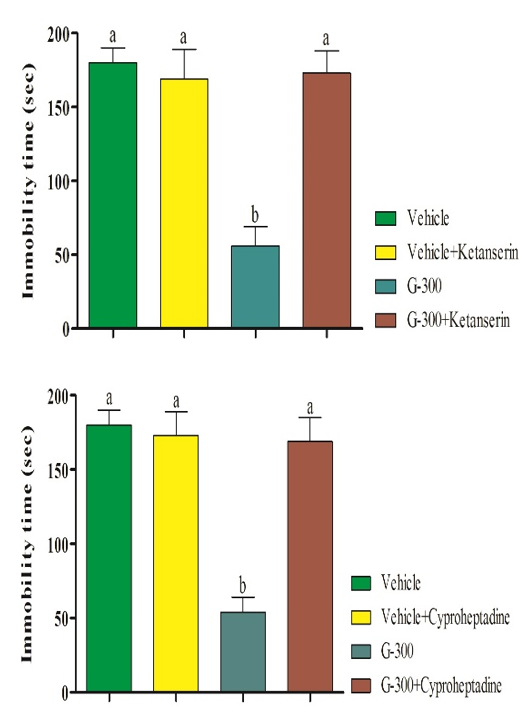

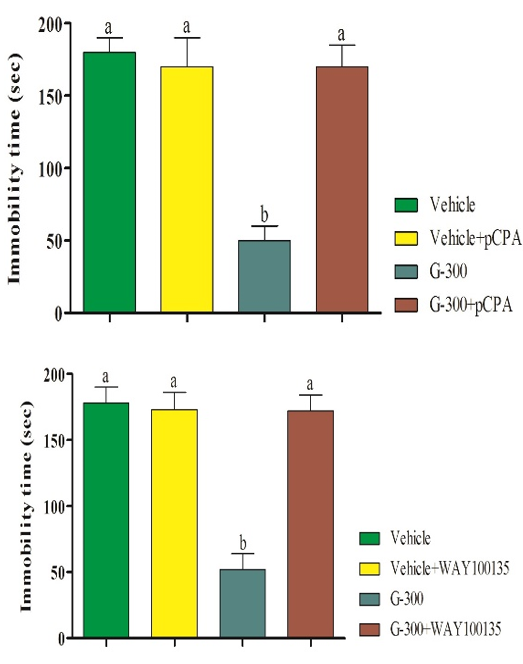

Pretreatments of mice with pCPA (preventer of serotonin synthesis), WAY100135 (receptor antagonist), ketanserin (5HT2A receptor antagonist), and cyproheptadine (5HT2 receptor antagonist) significantly prevented the antidepressant-like effect induced by the gingerol (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Pretreatment of mice with pCPA (preventorof serotonin synthesis), WAY100135 (receptor antagonist), ketanserin (5HT2A receptor antagonist), and cyproheptadine (5HT2 receptor antagonist) in antidepressant-like effect induced by gingerolin tail suspension test. Superscripts (a-c) show significant difference among groups. The data were analyzed by two-way ANOVA

Discussion

The present results showed that use of the gingerol as an antidepressant agent could express antidepressant-like activity in tail suspension test in mice. Tail suspension test has been known as one behavioral model for detection of antidepressant activity. In the model, decreased immobility time were considered as an indicator for antidepressant-like action [20]. Tail suspension test has been used to evaluate the depressive-like behaviors in mice because it could imitate helpless behaviors that frequently seen in patients with depression [28]. We did not observe differences for immobility time. Increased locomotor activity could be considered as false response. We could not find in the published literature any study to show antidepressant activity of gingerol.

With regards to our findings, it showed antidepressant-like effect of gingerol by modulation in serotonin system. The data for acute mechanism of antidepressant drugs caused to be considered by monoaminergic system [29]. The monoamine pathways such as serotonergic transmission have been known as target site for antidepressant drugs [30].

It has been accepted more or less that most of the drugs administrated for treatment of depression is involved in monoamine neurotransmitters [31]. However, pre-treatment with pCPA (preventer of serotonin synthesis), WAY100135 (receptor antagonist), ketanserin (5HT2A receptor antagonist), and cyproheptadine (5HT2 receptor antagonist) could prevent decreased immobility period induced by gingerol. It means that serotonergic system is involved in the antidepressant effects of gingerol in the tail suspension test in the mice. Previous studies have shown the role of 5HT as one neurotransmitter in depression, because it is involved in some symptoms of major depression [32]. Other reason is that 5HT1A receptors clearly modulate in the clinical effect of antidepressants [33] due to its position in the soma and dendrites of 5HT neurons in the dorsal raphe which inhibit to release 5HT [34]. Previous studies have also reported that ketanserin could prevent antidepressant activity in some herbal medicines in the tail suspension test in the animal model [31, 35]. It has been known tryptophan as substrate for synthesis of serotonin. We believed that gingerol could partly prevent oxidation of tryptophandue to its antioxidant properties. Unfortunately, we could not find any published study in the literature which showing effects of gingerol on serotonergic system.

Conclusion

Gingerol involves in serotonergic system and show antidepressant-like effect. We suggest touse the gingerol for treatment of depression as a novel agent in commercial preparation and prescribed as a drug for therapeutic reasons.

Acknowledgements: None declared by the authors.

Ethical Permissions: None declared by the authors.

Conflicts of Interests: None declared by the authors.

Authors’ Contribution: All authors contributed toward data analysis, drafting and revising the paper and agreed to be responsible for all the aspects of this work.

Funding/Support: None declared by the authors.

Major depressive disorder has been known a complex psychiatric disorder with unknown cause which will involve up to 20% of the individuals during their lifetime [1] and it causes disability in people [2]. It has been known to have some symptoms including adverse effects on mood, interest, feeling, hope, appetite, sleep, performance and social relationships [3].

Oxidative stress is result of excessive formation offree radicals and it is also attributed to antioxidant defense mechanism which maintains the cells removing free radicals [4]. Oxidative stress is involved in some psychiatric disorders [5, 6] which could be attributed to excessive oxygen consumption and lipid-rich compounds of the brain [7, 8]. Studies have related depression with faulted antioxidative enzyme activities [9-11].

The faulted antioxidant system could reduce the protection against reactive oxygen species (ROS) [9]. Elevated ROS in depression has been related with increased levels of malondialdehyde and arachidonic acid [9]. It has been reported increased oxidative stress in the rats exposed to stress [12]. These evidences suggest therapeutic activity of antioxidant compounds for treatment of depression [10]. 6-Gingerol is known as one phenolic compound which is found in some plants in Zingiberaceae family including ginger, cardamom and grain of paradise. It has been known to have some properties such as cognitive enhancer [13], anti-apoptotic [14], antioxidant and anti-inflammatory [15]. It has been reported effect of ginger on gastric similar to metoclopramide, a 5-HT4 receptor agonist with antagonist properties at 5-HT3 receptors through a selective 5-HT3 receptor antagonist [16, 17].

This study was thus conducted to evaluate the antidepressant-like activity of gingerol in mice model.

Materials and Methods

Materials

Gingerol powder and DMSO (Dimethyl sulphoxide) were purchased from Chromadex (Santa Ana, CA, USA) and Scharlo (Spain), respectively.

Animals

A number of 24 male NMRI mice, 4wk of age with 28±2g weight, were purchased from Pasteur Institute (Tehran, Iran). Those were maintained under lighting/darking program (12h:12h). Animals had free access to water and feed. Commercial feed was purchased from Razi Vaccine and Serum Research Institute (Karaj-Iran). All the used procedures were approved by National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (NIH Publications No. 8023, revised 1978).

Acute toxicity test

Previous procedures [18] were used to evaluate the acute toxicity test. Following 24 h food restriction,

24 mice were divided into 4 groups and intrapritoeanally received 200, 400, 800 and 1200mg/kg gingerol dissolved in DMSO. Following treatment, animals were considered for some toxicity signs and behavioral symptoms including locomotor activity, changes in physical appearancerespiratory distress, coma, and mortality for 72h. This action was conducted for 10 days and to be healthiness and mortality were recorded [19]. We did not observe any mortality and only dizziness was observed in levels of 800-1200mg/kg. Thus, we selected levels of 100 and 300mg/kg for future studies.

Tail suspension test

Tail suspension test was conducted as reported by previous studies and total period of immobility was considered as reported by previous studies [20]. Animals were divided into 4 groups with 6 mice and treated by follow protocol:

1) Vehicle group: mice intra pritoeanally received normal saline (10ml/kg);

2) G-100 mice intrapritoeanally received 100mg/kg gingerol;

3) G-200 mice intrapritoeanally received 200mg/kg gingerol; and

4) Fluoxetine: mice intra pritoeanally received 20 mg/kgfluoxetine.

To evaluate the tail suspension test, total period of immobility time was registered by using a chronometer. Decreased immobility time was considered as a criteria for antidepressant activity [21, 22].

Serotonergic system in the antidepressant-like effect of gingerol

To investigate the serotonergic system, pre-treatment with PCPA, blocker of 5HT synthesis, was conducted (once/d for 3consecutive days). Since the best responses were observed in 300mg/kg gingerol, same dose was used in future trials. Following pre-treatment with PCPA, animals were treated with 300mg/kg gingerol, 15min after last administration of PCPA. Animals were submitted to tail suspension test after administration of gingerol [23]. To evaluate the involvement of 5HT1 receptor, mice were pre-treated withWAY100135 (10mg/kg), treated with 300mg/kg gingerol60 min after pre-treatment and exposed to tail suspension test after administration of gingerol [24]. To assess the involvement the 5HT2 receptor, animals were pre-treated with ketanserin and cyproheptadine, treated with 300mg/kg gingerol 60 min after pre-treatment and finally submitted to ail suspension test [25, 26].

Open field test

To evaluate the psychomotor stimulant activity, OFT was conducted as reported by others [28]. Each mouse was grouped in Plexiglas boxes (40×60×50cm). All the crossings and rearing were registered. We considered crossing as locomotors activity and rearing as exploratory behavior.

Statistical analysis

The data were reported as mean± standard deviation (Mean±SD) and analyzed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Tukey post-hoc test was used to comparethe groups. A level of p<0.05 was considered assignificant. The figures were illustrated by Prism 7 (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA).

Findings

Administration of gingerol could significantly decrease immobility time (p<0.05). Immobility was decreased with increasing dose, so that lowest immobility time was observed in mice administrated with 300mg gingerol. There was no significant difference between fluoextine with 300mg gingerol (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Effect of intra-pritoeanal administration of 6-gingerol in tail suspension test. The data are shown in mean±SD. Superscripts (a-c) show significant difference among groups. The data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA

Number of OFT was not different among different groups (p>0.05; Figure 2).

Figure 2. Effect of gingerol in OFT in mice.The data are shown in mean±SD. Superscripts (a-c) show significant difference among groups. The data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA

Pretreatments of mice with pCPA (preventer of serotonin synthesis), WAY100135 (receptor antagonist), ketanserin (5HT2A receptor antagonist), and cyproheptadine (5HT2 receptor antagonist) significantly prevented the antidepressant-like effect induced by the gingerol (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Pretreatment of mice with pCPA (preventorof serotonin synthesis), WAY100135 (receptor antagonist), ketanserin (5HT2A receptor antagonist), and cyproheptadine (5HT2 receptor antagonist) in antidepressant-like effect induced by gingerolin tail suspension test. Superscripts (a-c) show significant difference among groups. The data were analyzed by two-way ANOVA

Discussion

The present results showed that use of the gingerol as an antidepressant agent could express antidepressant-like activity in tail suspension test in mice. Tail suspension test has been known as one behavioral model for detection of antidepressant activity. In the model, decreased immobility time were considered as an indicator for antidepressant-like action [20]. Tail suspension test has been used to evaluate the depressive-like behaviors in mice because it could imitate helpless behaviors that frequently seen in patients with depression [28]. We did not observe differences for immobility time. Increased locomotor activity could be considered as false response. We could not find in the published literature any study to show antidepressant activity of gingerol.

With regards to our findings, it showed antidepressant-like effect of gingerol by modulation in serotonin system. The data for acute mechanism of antidepressant drugs caused to be considered by monoaminergic system [29]. The monoamine pathways such as serotonergic transmission have been known as target site for antidepressant drugs [30].

It has been accepted more or less that most of the drugs administrated for treatment of depression is involved in monoamine neurotransmitters [31]. However, pre-treatment with pCPA (preventer of serotonin synthesis), WAY100135 (receptor antagonist), ketanserin (5HT2A receptor antagonist), and cyproheptadine (5HT2 receptor antagonist) could prevent decreased immobility period induced by gingerol. It means that serotonergic system is involved in the antidepressant effects of gingerol in the tail suspension test in the mice. Previous studies have shown the role of 5HT as one neurotransmitter in depression, because it is involved in some symptoms of major depression [32]. Other reason is that 5HT1A receptors clearly modulate in the clinical effect of antidepressants [33] due to its position in the soma and dendrites of 5HT neurons in the dorsal raphe which inhibit to release 5HT [34]. Previous studies have also reported that ketanserin could prevent antidepressant activity in some herbal medicines in the tail suspension test in the animal model [31, 35]. It has been known tryptophan as substrate for synthesis of serotonin. We believed that gingerol could partly prevent oxidation of tryptophandue to its antioxidant properties. Unfortunately, we could not find any published study in the literature which showing effects of gingerol on serotonergic system.

Conclusion

Gingerol involves in serotonergic system and show antidepressant-like effect. We suggest touse the gingerol for treatment of depression as a novel agent in commercial preparation and prescribed as a drug for therapeutic reasons.

Acknowledgements: None declared by the authors.

Ethical Permissions: None declared by the authors.

Conflicts of Interests: None declared by the authors.

Authors’ Contribution: All authors contributed toward data analysis, drafting and revising the paper and agreed to be responsible for all the aspects of this work.

Funding/Support: None declared by the authors.

References

1. Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):617-27. [Link] [DOI:10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.617]

2. Kessler RC, Bromet EJ. The epidemiology of depression across cultures. Annu Rev Public Health. 2013;34:119-38. [Link] [DOI:10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031912-114409]

3. Wallace CJK, Milev R. The effects of probiotics on depressive symptoms in humans: A systematic review. Annu Gen Psychiatry. 2017;16:14. [Link] [DOI:10.1186/s12991-017-0138-2]

4. McCord JM. Human disease, free radicals, and the oxidant/antioxidant balance. Clin Biochem. 1993;26(5):351-7. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/0009-9120(93)90111-I]

5. Bouayed J, Rammal H, Soulimani R. Oxidative stress andanxiety relationship and cellular pathways. Oxidative Med Cell Longevity. 2009;2(2):63-7. [Link] [DOI:10.4161/oxim.2.2.7944]

6. Hovatta I, Juhila J, Donner J. Oxidative stress in anxiety and comorbid disorders. Neurosci Res. 2010;68(4):261-75. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.neures.2010.08.007]

7. Halliwell B. Oxidative stress and neurodegeneration: Where are we now?. J Neurochem. 2006;97(6):1634-58. [Link] [DOI:10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.03907.x]

8. Berk M, Ng F, Dean O, Dodd S, Bush AI. Glutathione: Anovel treatment target in psychiatry. Trend Pharmacol Sci. 2008;29(7):346-51. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.tips.2008.05.001]

9. Maes M, Galecki P, Chang YS, Berk M. A reviewon the oxidative and nitrosative stress (O&NS) pathways in major depression and their possible contribution to the (Neuro) degenerative processes in that illness. Progr Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2011;35(3):676-92. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.pnpbp.2010.05.004]

10. Scapagnini G, Davinelli S, Drago F, de Lorenzo A, Oriani G. Antioxidants as antidepressants: Fact or fiction?. CNS Drugs. 2012;26(6):477-90. [Link] [DOI:10.2165/11633190-000000000-00000]

11. Erel O. A novel automated direct measurement method for total antioxidant capacity using a new generation, more stable ABTS radical cation. Clin Biochem. 2004;37(4):277-85. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2003.11.015]

12. Lucca G, Comim CM, Valvassori SS, Réus GZ, Vuolo F, Petronilho F, et al. Increased oxidative stress in submitochondrial particles into the brain of rats submitted to the chronic mild stress paradigm. J Psychiatr Res. 2009;43(9):864-9. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2008.11.002]

13. Saenghong N. Zingiber officinale improves cognitive function of the middle-aged healthy women. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2012;2012:383062. [Link] [DOI:10.1155/2012/383062]

14. Seo HB, Kwon TD, Song YJ. The effect of ginger extract ingestion and swimming exercise on insulin resistance and skeletal muscle antioxidant capacity and apoptosis in hyperglycemic rats fed a high-fructose diet. J Exerc Nutr Biochem. 2011;15(1):41-8. [Link] [DOI:10.5717/jenb.2011.15.1.41]

15. Surh, YJ. Molecular mechanisms of chemopreventive effects of selected dietary and medicinal phenolic substances. Mutat Res. 1999;428(1-2):305-27. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/S1383-5742(99)00057-5]

16. Yamahara J, Huang Q, Li Y, Xu L, Fujimura H. Gastrointestinal motility enhancing effect of ginger and its active constituents. Chem Pharm Bull (Tokyo). 1990;38(2):430-1 [Link] [DOI:10.1248/cpb.38.430]

17. Sharma SS, Gupta YK. Reversal of cisplatin-induced delay in gastric emptying in rats by ginger (Zingiber officinale). J Ethnopharmacol. 1998;62(1):49-55 [Link] [DOI:10.1016/S0378-8741(98)00053-1]

18. Lorke D. A new approach to practical acute toxicity. Arch Toxicol. 1983;54(4):275-89. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/BF01234480]

19. Kumar N, Kumar Gupta A. Wound-Healing Activity of Onosma hispidum (Ratanjot) in Normal and Diabetic Rats. J Herb Spice Med Plant. 2010;15(4):342-51. [Link] [DOI:10.1080/10496470903507924]

20. Steru L, Chermat R, Thierry B, Simon P. The tail suspension test: A new method for screening antidepressants in mice. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 1985;85(3):367-70. [Link] [DOI:10.1007/BF00428203]

21. Jesse CR, Wilhelm EA, Bortolatto CF, Nogueira CW. Evidence for the involvement of the noradrenergic system, dopaminergic and imidazoline receptors in the antidepressant-like effect of tramadol in mice. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2010;95(3):344-50. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.pbb.2010.02.011]

22. Voiculescu SE, Rosca AE, Zeca V, Zagrean L, Zagrean AM. Impact of maternal melatonin suppression on forced swim and tail suspension behavioral despair tests in adult offspring. J Med Life.2015;8(2):202-6. [Link]

23. Harkin A, Connor T, Walsh M, St John N, Kelly J. Serotonergic mediation of the antidepressant-like effects of nitric oxide synthase inhibitors. Neuropharmacology. 2003;44(5):616-23. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/S0028-3908(03)00030-3]

24. Tanyeri P, Buyukokuroglu ME, Mutlu O, Ulak G, Akar FY, Celikyurt IK, et al. Involvement of serotonin receptor subtypes in the antidepressant-like effect of beta receptor agonist Amibegron (SR 58611A): An experimental study. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2013;105:12-6. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.pbb.2013.01.010]

25. Gu L, Liu YJ, Wang YB, Yi LT. Role for monoaminergic systems in the antidepressant-like effect of ethanol extracts from Hemerocallis Citrina. J Ethnopharmacol. 2012;139(3):780-7. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.jep.2011.11.059]

26. Zheng M, Li Y, Shi D, Liu C, Zhao J. Antidepressant-like effects of flavonoids extracted from Apocynum Venetum leaves in mice: The involvement of monoaminergic system in mice. J Ethnopharmacol. 2013;147(1):108-13. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.jep.2013.02.015]

27. Brown RE, Corey SC, Moore AK. Differences in measures of exploration and fear in MHC-congenic C57BL/6J and B6-H-2K mice. Behav Gen. 1999;29:263-71. [Link] [DOI:10.1023/A:1021694307672]

28. Porsolt RD, Bertin A, Jalfre M. "Behavioural despair" in rats and mice: Strain differences and the effects of imipramine. Eur J Pharmacol. 1978;51(3):291-4. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/0014-2999(78)90414-4]

29. Berton O, Nestler EJ. New approaches to antidepressant drug discovery: Beyond monoamines. Nature Rev Neurosci. 2006;7(2):137-51. [Link] [DOI:10.1038/nrn1846]

30. Xu Y, Wang Z, You W, Zhang X, Li S, Barish PA, et al. Antidepressant-like effect of trans-resveratrol: Involvement of serotonin and noradrenaline system. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2010;20(6):405-13. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.euroneuro.2010.02.013]

31. Risch SC, Nemeroff CB. Neurochemical alterations of serotonergic neuronal systems in depression. J Clin Psychiatry.1992;53:3-7 [Link]

32. Haider S, Khaliq S, Haleem DJ. Enhanced serotonergic neurotransmission in the hippocampus following tryptophan administration improves learning acquisition and memory consolidation in rats. Pharmacol Rep. 2007;59(1):53-7. [Link]

33. Celada P, Puig MV, Amargós Bosch M, Adell A, Artigas F. The therapeutic role of 5-HT 1A and 5-HT 2A receptors in depression. Psychiatry Neurosci. 2004;29(4):252-65. [Link]

34. Shrestha S, Hirvonen J, Hines CS, Henter ID, Svenningsson P, Pike VW, et al. Serotonin-1A receptors in major depression quantified using PET: Controversies, confounds, and recommendations. Neuroimage. 2012;59(4):3243-51. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.11.029]

35. Machado DG, Bettio LE, Cunha MP, Capra JC, Dalmarco JB, Pizzolatti MG, et al. Antidepressant-like effect of the extract of Rosmarinus officinalis in mice: Involvement of the monoaminergic system. Prog Neuro Psychopharmacol Biol Psychiatr. 2009;33(4):642-50. [Link] [DOI:10.1016/j.pnpbp.2009.03.004]